|

| Typhoon Hope, 1979 |

You could read the signs of an approaching typhoon a day or two beforehand: leaden sky, grey-blue clouds, sultry oppressive atmosphere, drop in air pressure. When the storm approached within a certain distance of Hong Kong, the Royal Observatory In Kowloon would hoist the No. 1 signal and broadcast hourly weather reports through Radio Hong Kong, describing the storm's central wind speed, distance from Hong Kong, speed with which it was travelling, its present course, and the time it would take to reach Hong Kong if it continued on Its present course. Big ships in the harbour would cut short their stay and depart. Other ships on their way to Hong Kong would stay clear. Aircraft would do the same. Fishing vessels, lighters, yachts, and small harbour craft would hurry to the several typhoon shelters and pack tight; the tighter, the safer.

Prudent residents would bring indoors all moveable objects from outside (verandah furniture and flowerpots), to avoid their being blown through windows. Windows would be firmly closed and the premises battened down. Shopkeepers would cease business and pull down the metal roller blinds over their glass shop fronts (metal roller blinds were a common feature, pulled down every day at the end of the trading day to avoid burglary).

No. 2-6 signals from the Royal Observatory denoted the direction of the storm and its closer approach. By the time No. 7 was hoisted, the wind would be blowing hard and the rain crashing down. At that stage, Hong Kong would be closed down and all outdoor or business activity had ceased. Hong Kong would be out of action until the typhoon had departed and its aftermath cleared up. The government in London and some overseas commercial organisations could not comprehend such a situation, convinced that ordinary business must continue as usual. They could not understand the danger outside from flying objects and the virtual Impossibility of standing upright and moving about.

For the ordinary householder, the ordeal began as the wind increased to a terrifying shriek. When it reached over 100 mph it could be really frightening.

|

| Typhoon Rose, 1971 |

Coupled with the wind was the rain blowing horizontally. No matter how tightly windows were closed, the wind would work latches loose and force the rain through the sides in a never ending stream of water. If there were doubts whether the glass on the windward side could withstand the wind or a flying object, it was wise to evacuate the room for a safer place. Great care had to be taken, even indoors. Wind pressure tore the door free, trapping your finger as the door slammed shut. Wind pressure on one side meant equal suck on the other.

Although a typhoon could be moving in a certain direction, the accompanying winds revolved in a circle round it. This meant that, if there were a direct hit on Hong Kong, wind would be blowing from one quarter until the centre reached the territory. There would then be a brief lull (the eye of the typhoon) before the wind rose again, blowing from the opposite quarter.

|

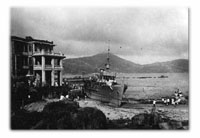

| Typhoon, 1937 |

Not every typhoon making for Hong Kong reached the territory with a direct hit. sometimes it could change direction, brushing past with a middling blow; destructive but not catastrophic. But it was always necessary to prepare for the worst, and to remember that more than one typhoon could occur during the season. But, even if the typhoon was only a brush-past, it could still be destructive if combined with a tidal surge. The wind damage on land was usually made worse by the heavy rain which could cause land slips (particularly on the steep slopes of Hong Kong), dislodged boulders, house collapse, and flooding. As soon as the storm had passed, emergency services would be busy saving life, restoring electricity and water, and clearing blocked roads and drains. Trees exposed to the wind would be stripped of leaves which then formed a slippery coating on roads.

An interesting feature was that, where a deciduous flowering tree had lost its leaves, a few weeks later it might flower again (twice in the same year), presumably because its seasonal rhythm mistook the loss of leaves for the end of winter and therefore time to start flowering and putting on new leaves.

The modern development of radar, weather balloons, and satellites has made it easier to locate and plot the course, speed, and intensity of typhoons. For the 30 or so years after the Pacific war ended. Hong Kong relied for much of its weather information on the American weather bureau at the former Clark Field military base in the Philippines. Typhoons there were always given girls' names. According to cynics, this reflected the fickle female nature of typhoons in frequently changing course. These days, affirmative action seems to have resulted in the introduction of boys' names or even local ethnic names. Indeed, the work "typhoon" is too often replaced by "cyclone", losing much of the charm of a traditional local word.