|

| Training Surveyors, 1965 |

The prospect of a tough and itinerant lifestyle called for physical fitness and a level of self-sufficiency to cope with emergencies and crises but as I set out I didn't know what demands the life might make upon me. I had little regard for the possible loneliness, repeated hardships, illness in remote places far from medical aid, how I would adjust to local people and their values, the effects of disagreements amongst fellow expatriates and the homesickness and privations of an unaccustomed way of life. I had never experienced the discomforts of tropical weather and mosquitoes and had no inkling of the monotony and uncontrollable irritability and discomfort of long enervating days and lonely nights. But the hazards acted as an incentive and tended to be blindly ignored, as indeed they would be by the young of today; the minutiae I was to experience first hand. The wise words of Mary Kingsley in the late 1800s were ignored, and I think I was right to do so:

'When you have made up your mind to go to West Africa the best thing you can do is to get it unmade and go to Scotland instead'

But another great pioneer, Mary Gaunt, said:

'A land of immense possibilities

Heat fever and mosquitoes

Gorgeous nights and divine mornings

A white man's grave -

But live wisely and discreetly

And it is no more likely to be there than anywhere else'

I was not sure I wished to stay in Africa very long and thought two tours of 18 months as Nigeria approached its independence might be enough for me. The fact that I served for 20 years says a lot about me, but probably says more about Nigeria and Nigerians. I knew it could never be my permanent home but there were times when it seemed that it was, when things were going well, when work was very satisfying and when I was so busy there was little time to think about the future. If I survived the obvious risks some day the break would have to be made.

|

| Advanced Survey Course |

Independence in 1960 brought in an inexperienced democracy controlled by a political elite followed by military coups, a civil war and territorial fragmentation into States. Despite periodic turmoil, uncertainty and chaos my work, as it changed from practical to administrative, continued for some years to be satisfying and rewarding. There was reassurance that the surveyor's expertise and experience were acknowledged and valued. With only a few exceptions there was goodwill all round. Those exceptions were mostly found amongst those who were new to the reins of authority, lacked technological understanding, had received little or no training in administration, and did not possess a natural bent to lead. Military violence and the arming of large numbers of people had engendered a dangerous and unlawful malaise; extortion, robbery and violence threatened to become everyday events. In spite of the well-intentioned changes to the country's administrative structure regional, district, religious and ethnic differences and aspirations remained threats to the stability of the nation.

Legally enforceable property rights have provided the basis for economic development in all the major successful countries of the world. Resources, size and a burgeoning population gave Nigeria the potential to be a prosperous leader in Africa but there was a need to awaken the dormant capital that lay locked up in its land resources. If rights in land are not properly documented, assets cannot be turned into useable capital, cannot be used as an investment and cannot be traded other than locally amongst those who trust each other or who have traditionally exercised control over that land. There is a risk of a weakened or black economy based on untrustworthy businesses conducted without proper documentation. The key to a system of secure and demonstrable rights in land which cannot be held in freehold, with little risk of counter claims, and which can be used as collateral, is an efficient cadastral system backed by fast and efficient land surveying and an open and dependable land register. Obtaining rights of occupancy swiftly, and with permission to develop, has to be within the reach of ordinary people, free of any burden of bribery and corruption.

Colonial policies had ensured that local customs and values had never disappeared and most land was held unsurveyed under customary title. This was not however acceptable as security for development loans and trading and resulted in a burgeoning demand for the alternative, certified statutory leasehold titles supported by surveyed plans of demarcated land, an internationally accepted cadastral system enshrined in law. With a severe shortage of capable manpower it became impossible to keep pace with demand without the introduction of innovative aerial photographic techniques not understood by local influential land officers and to which certain entrenched interests were opposed. Blatant corrupt practices, abhorrent to my professional principles, found ways to resist improvements and to retain and undermine the security and integrity of the system I was employed to operate and it was time to leave. My signature was valued and I was urged to stay on but I thought it better to depart while my hosts were reluctant to lose me.

|

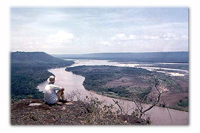

| An Office With a View |

Vindication of my decision came from an Assistant Surveyor-General of one of the northern States, whom I had first appointed as a trainee Survey Assistant in 1971. In a personal letter written to me in 1988, over a decade after my departure, he said:

"We have not been able to build upon the foundation you laid partly due to poor resources and deliberate administrative bottlenecks, and partly due to interference. We just work to earn a living, not for job satisfaction"

In many ways I was sad to leave. I was enriched by my time in Northern Nigeria, enjoyed the challenges and responsibilities which came my way, the variety, the travelling, the gratification of standing alone on remote summits, the light, the colour, the pleasure of relaxation after a hard day's physical work in the blistering heat, the friendships I made, many of them surviving to this day, the camaraderie of those with whom I shared the experience. But most of all I enjoyed helping to train my local successors and meeting and working with so many of the diverse, fascinating, welcoming and very likeable Nigerian people. West Africa had a way of taking root in the imagination, a strange combination of love and hatred, regardless of its hazards and there always resided a muted but persistent desire to return. In a strange way I feel sorry for those who never fell under this spell. I cannot forget Africa, and although I know it could so easily forget me I feel, as many others have found when they revisited their former domains, that I would be welcomed back as a helpful friend and not as the arrogant colonial oppressor so hackneyed by prejudiced imperial critics. It continues to surprise me that in spite of the difficulties and unpleasantness of the later years when water, power and fuel supplies broke down and when medical and financial services deteriorated, that I survived so long and that optimism and a strong attachment to Africa prevailed. It can be a mistake to revisit old familiar places after the lapse of time, the disappointments can be too great, as indeed I fear they would be if I returned to Borno, but in spite of this I still harbour a desire and a curiosity to see once again the land that remains part of me.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.