| In memory of all those gallant young men in the Royal Malayan Police who risked, and sometimes gave, their lives during the Emergency. | ||||||||

| Foreword | ||||||||

| More used to reviewing rather than fore wording books, the first thing to say, in either capacity, is that for me this is utterly engaging. Academic reviewers often sniff at volumes of essays or conference proceedings - 'uneven quality' etc. - but academic reviewers seldom live dangerously. Nor do they always know how it feels. This is real. The body of evidence compared to the bones or structure of scholarly argument. Some of it is delightfully inconsequential: but so is quite a lot of family history. Some of it only lifts a corner of the curtain - for example, on Nicol Gray - although far enough. for inference and to modify opinions, even if one is still looking for the full Monty. At the highest-level one wonders why no one mentions Arthur Young nor, for that matter Langworthy, Jenkin or Madoc. But this, again, reveals the historian's predisposition to believe that change comes from the top rather than from the bottom. For me and for anyone else who may still need convincing, the overwhelming importance of what happened at the bottom is hereinafter revealed. Yes, it was fortuitous that as soon as the Mandate in Palestine ended, the Emergency in Malaya began. But how kampong Malays and British police lieutenants bonded to produce the indispensable security for the rubber estates and just how much work went into creating a special constabulary from nothing is certainly something that has hardly been taken into account, at least by me. One knows that for every soldier who was killed, two policemen died. Not a lot of people, however, would know how fraught the situation was at the beginning and that police lieutenants could be killed within days of arrival without firing a shot. And there are few who have known the eventual, awful and terminal silence of ambush as well as the mayhem and fury when it begins. These are the unaffected and understated accounts of those who were at the sharp end. There is some very fine writing. If I were to mention one or two pieces, they would be those on 'Q' operations: because the authors had more space for their narrative; and because they had me dry-mouthed with fear and excitement. Also, for the historian, the revelation that half of the remnants of an Armed Work Force - admittedly down to four in September 1956 - were women and that a woman State Committee Member in Negri Sembilan had another female comrade as her second in command. Elsewhere there is humour, pathos, and a glorious piece of near libel on visitors from Westminster. There is the unaffected charm of the animal stories and snippets, a reminder not to bounce your Sten gun on the ground and so many changing pictures, shapes and colours as to produce a genuine, old-fashioned kaleidoscope. Presumably this is what Brian Stewart had in mind: but it is astonishing, nevertheless. At an age when he might reasonably have put on his carpet slippers, to have sought out and compiled these fust-hand testimonies has given us a monument to the Royal Malayan Police. Many of the experiences were shared. Each of these accounts is unique. I hope it is not too sentimental to see it as a remarkable family history; and I am honoured that Brian has asked me to write this foreword. May I, in turn, honour the achievements, the bravery, and the steadfastness of those who served, and especially those who died. Anthony Short | ||||||||

| Preface | ||||||||

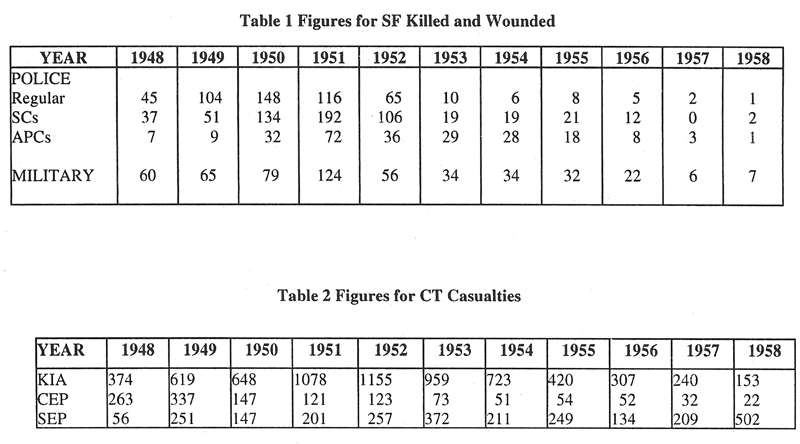

| Many books have been written about the war which erupted in Malaya in 1948 and was known, for legal reasons, as an 'Emergency'. There have been histories, accounts by authors and journalists, academics, soldiers and by former police officers, such as Dato Mohd Pilus Yusoh, Dato' J. J. Raj (Im.), Dato' Seri Yuan Yuet Leng, Mr Leong Chee Woh, Mr R Thambapillay and Roy Follows, Leon Comber and the late John Slimming. But none of these authors took as a central theme the role and performance of the police in that bitterly fought war, nor did they deliberately attempt, as this book does, to record the voices of the junior police officers who fought in what General Templer was quick to recognise as a 'Subalterns' war. Thomas Grey, the 18th Century poet, said, "Any fool can write a valuable book if he will only tell us what he heard and saw with veracity." I have tried to follow Grey's precepts. The book is not only intended to record the voices of the subalterns and, where possible, of their men, but also to pay tribute to the many policemen who sacrificed their lives in the fight for freedom, and to all the gallant men who fought alongside them during the campaign. In 1952, the worst year for police casualties, 350 police, of all ranks, races and branches, lost their lives in action. We salute their memory. When I suggested this book, I captioned my proposal Operation Sharp End, a phrase chosen to emphasise that my central objective was to record memories of junior officers who bore the brunt of the fight on the ground. Of course, some of those junior officers, who survived and continued their police career in Malaysia, finished up as distinguished senior officers, but it is their memories as juniors, not their later reflections, which appear in this book. In the course of preparation I received a lot of material, which was not all about battles, ambushes, patrols and operations, and tales of derring-do in the face of the enemy. The book, therefore, has stories of events 'behind the lines' and 'off duty', even of ghosts and magic. Although most of the text was specially written for Operation Sharp End some of it consists of extracts taken with the permission of the authors, from articles and books' which they have already published. I hope that the book may occasionally cast some new light on the complicated events of those far off days, but that is certainly not its central purpose. The army and the police both performed magnificently, fighting side-by-side in many cases. But whereas some of the voices of the soldiers who participated in the fight have been recorded in regimental hIstones, there has been no equivalent literature recording the police voices, and so this book was born of a wish to e;sure that police voices could also be 'heard'. !though I never had the honour of serving in the Royal Malaysia Police, I did spend the best part of twenty years working WIth them as a Malayan Civil Service officer a diplomat and, finally, for four years as Director of the Rubber Growers Association, where I was in charge of 2,500 auxiliary policemen (APs) guarding the estates. I have, as a result, a lot of friends in the police force, and a very high regard for their serVIce. When, after fifty years or so, I returned to Scotland and was invited to join the RMPFOA it occurred to me that there was probably sufficient material available to form the basis for a book of reminiscences and anecdotes by people who had served during the Emergency. The Association agreed. Of course, we have started Operation Sharp End very late, but better late than never; we owe it to the families and descendants of all those who served in the Emergency to ensure that the overviews should be complemented by more individual memories and anecdotes. There is seldom a mention of the voices in the field in the books written by senior officers, whose books therefore give little flavour of the realities of action. A typical military example might be, "The advance ran into heavy resistance and It took several hours to drive the enemy out of their positions." But this passage does not tell us that the subaltern commanding the leading platoon and the platoon sergeant were both killed in the battle, that the platoon suffered fifty percent casualties from well-sited machine-guns, or how a corporal rallied the survivors and mounted a second attack, skilfully using mortar smoke to conceal his movements and, finally, leading a bayonet charge to dislodge the enemy. Nor does such a history tell us that the corporal won a Military Medal. And we know nothing of the thoughts of the men engaged in the battle; and how they overcame fear of death and wounds. In short, the two-line summary tells us nothing about the human dimension.for the sort of book we are attempting here. In the 1960s a British farmer, visiting the war graves of Flanders, was so moved by the thought of the carnage at the Battle of the Somme that he pulled together the memories of survivors of all ranks. I found a moving quotation from this book: The Tyneside Scottish were advancing across the moonscape of No Man's Land toward the German trenches, where, despite the heaviest bombardment of all time, the Germans were still in fighting trim, and the bullets from their machine-guns were mowing down the advancing infantry. In one company only a subaltern, a platoon sergeant and a private reached the objective. The private recalled, "We had started out as a Company of over a hundred men, but now there were only three of us; the lieutenant looked round and said; "God, God Where are the rest of the Company?" There are many obvious objections to this type of history; memories are selective, and fade and play tricks. The contributors are self-selecting: many people who have a story to tell will not tell it. During my efforts to collect stories from the survivors of a battle in 1944, I once asked a Jock (Scottish soldier) to tell me what he remembered of a twelve-hour battle when his platoon was constantly on the move, carrying ammunition and the wounded to and from the front line. All I could drag out of him was, "Och! I suppose it was pretty rough." But although it is sometimes like drawing teeth trying to extract memories, I believe the effort is worthwhile, and I hope that the collection that follows will find merit with readers who want to know what sort of men were leading the police at the Sharp End during the Emergency, and what they thought about. In August 2001, having received a large number of manuscripts as a result of our original appeal for anecdotes, and scoured the libraries for relevant material, I visited Malaysia to seek further material. I knew the visit would be fun since the Malaysians are probably the most friendly and welcoming people in the world. But I did not anticipate the astonishing kindness, helpfulness, and encouragement with which Michael Thompson, who kindly accompanied me, and were received. My hosts, Datuk and Datin Moggie, gave us the run of their comfortable home, and the use of a car and driver. Former Inspector General of Police (IGP), Tun Hanif, invited a vast gathering of former friends and colleagues, exministers, retired generals, and highly decorated police officers, to launch our 'Seminar', and provided us with an office where we could conduct our discussions. The younger generations in Britain have been brainwashed into believing that our colonial history was shameful, and Whitehall always tended to assume that we would be persona non grata if we ever showed our faces in our former territories. It is a pity that none of them have experienced the reality: not just politeness, but full-blooded cooperation, warm friendship and mutual respect. Whatever else the Seminar accomplished, it gave me confidence that my Malaysian friends approved of Operation Sharp End.

Readers coming to this book at the beginning of the 21s1 Century may find. our fear of the Communist Revolution bizarre. But in 1948 the threat seemed real enough. We had, at crippling cost, just won a war against Hitler to stop him dominating the world, and now the Soviet Union was sprawling over Eastern Europe and half of Germany, and boasting that Communism would bury capitalism. It is easy now to see that the giant had feet of clay, but at the time the size of the bear, his victories over Hitler's best troops, and his belligerence, could not easily be ignored. Meanwhile in Asia, Mao Tsetung was thrashing the Chinese Nationalists; the French in Vietnam were finding it increasingly hard to contain the Vietcong, and Sukamo, having forced the Dutch out of the Netherlands East Indies, had allied himself with Communist China. You did not have to be a professional cold war warrior to conclude that Communism posed a serious threat. At a time when all round the world terrorism continues to defy civilised societies, it will be noted that in Malaya we defeated a strong terrorist force relying more on intelligence than on weaponry, and on brains as much as on courage. I hope that readers will share some of the pleasure that I have derived from this project. It is an exercise in nostalgia for all of us who were involved but also, I hope, a contribution to an understanding of the young men who were plunged in at the deep end, often with minimum or even no training, and achieved near miracles in the face of a determined, jungle-trained and experienced enemy. I salute them. They did wonders! | ||||||||

| Introduction | ||||||||

Malaya was a plural, not an integrated, society. No one pretended that all the races were the same, but the bangsa, for the most part, tolerated each other's different cultures and beliefs. Inevitably there was some resentment at the growing economic power of the immigrants, who now represented half the population, but tolerance, not pogrom, was the norm in Malayan society. The Malay Peninsula stretches for about 550 miles: from Thailand in the north to Singapore in the south. It is lapped on the east by the South China Sea and on the west by the 'Straits of Malacca. Mountains running down the centre divide the east with its stretches of golden beaches and agricultural and fishing economy from the west with its tin mines and plantations. In 1948 there were main roads running from north to south on both sides of the peninsula, the main railway line ran from Thailand to Singapore, through KL, the Federal capital. A Department of Information leaflet of the time described The backbone of mountains, the highest over 7000 ft, is covered in primary and secondary evergreen jungle. One fifth of the country consists of rubber estates, tin mines, rice fields, towns and villages: four fifths is trackless forest and undergrowth so dense that a man is invisible at twenty-five yards. The average noon temperature is 90° and there is torrential rain almost every day. The primary jungle can be spectacularly beautiful with tree trunks hundreds of feet high, standing like the pillars of some great cathedral, its roof a green canopy of leaves and ferns. The secondary jungle however is quite another matter. Scrubby belukar, a tangle of bushes, saplings, thorny plants, tough creepers and sturdy bamboo, combine to create a nearly impenetrable barrier requiring heavy work with a parang (short bladed sword) to force a path. Torrential rains and the accompanying humidity rot equipment and uniform, which then rubs the skin off in the tenderest parts of the body. Leeches search assiduously for an opening in boots or clothes that allow them to get at the victim's blood, while mosquitoes, ants and midges seek his flesh. It was this trackless forest that made up eighty per cent of the country and was the scene of most operations. Constitutionally Malaya had, since the 19th Century, been a loose association of Malay States, ruled by Malay monarchs but accepting protection and advice from Britain, linked through the British connection to the three Straits Settlements: Malacca, Penang and Singapore.

The normal tranquillity of the political scene had been disturbed after the war by a misguided Colonial Office attempt to replace. the loose pre-war association of Federated and Unfederated States with a centralised system under a new constitution, The Malayan Union (MU) was designed not only to centralise and tidy up but also to improve the constitutional position of the immigrants. Although the Rulers reluctantly agreed to accept the new constitution, it was not long before the Malays began to protest publicly. London retreated and by early 1948 a new Federal constitution, which took fuller account of Malay sensitivities, had been agreed. Perhaps someone had taken heed of the Malay proverb, Sisat di ujong jalan, balek ka pangkal jalan: 'If you lose your way, go back to the beginning of the road'. Malaya reverted to its normal decorous mode in which political discussion tended not to take place in riotous assembly. The immigrant interest in legal rights was much weaker at grass roots level than Britain's metropolitan reformers had imagined. This was hardly surprising since they had emigrated to Malaya for economic, not for political, reasons. Communist ideas had been circulating in Malaya since the 1920s. In 1939, adopting the Moscow line, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) had opposed the war against Germany and fomented strikes to damage the war effort. The Party line was, of course, changed when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and the Malayan Communists joined the British in a temporary alliance against the Japanese invaders. After the Japanese surrender the MCP claimed that it had been responsible for the defeat of the Japanese, a claim that many believed. The MCP then returned to its subversive ways, flexing its muscles through domination of organisations such as the Trade Unions, the China Democratic Youth League, Chinese schools and the Chinese press, all of which formed part of what they called a United Front. But their subversive activities were not limited to propaganda and industrial action: their henchmen were using torture and murder. Although there was a small Malay element in the MCP, and also a small Indian element, the MCP was in essence a Chinese party drawing the vast majority of its members from Chinese immigrant families of relatively recent arrival, and educated, if at all, in Chinese language schools. Such people had minimal interest in integration into their host society, unlike the long resident Chinese, such as the Straits Chinese, who had learnt Malay and English, and saw themselves as Malayans. The MCP had been encouraged to revive their wartime dreams of taking over Malaya by the triumph of the Soviet Union in Europe and, even more, by the dramatic victories of Mao Tsetung in China where, despite massive US aid to President Chiang Kai Shek and his party, the Communists were winning. In early 1948 the Central Committee of the MCP directed that plans should be made to launch a countrywide armed insurrection. At this time, although the country had not fully recovered from the ravages of war, the economy was developing well. There was a strong demand for Malaya's staple exports, rubber and tin, and in Malaya's benign environment even the poorest could find food, clothing and materials to build a simple shelter. There were no starving masses, no armies of hungry, angry, dispossessed peasants, or downtrodden, unemployed proletariat festering in city slums, to exploit. By almost any standard, Malaya was a fortunate country. The people, whatever their race, were for the most part content with their lot and there was little of the political tension, which had characterised the relations between the metropolitan power and the local politicians in India during the last years of the Raj. The MCP, however, was determined to turn this tolerant and relatively successful society into a People's Republic, persuading the population to cooperate, if necessary by intimidation, torture and murder. It is difficult to understand why the MCP should have thought that tolerant, prosperous Malaya was ripe for revolution. The situation could hardly have been more different from that in China where decades of civil war, vicious corruption and runaway inflation under the maladministration of the Kuomintang (KMT) had persuaded the vast majority of the Chinese, regardless of their political views, that any other government, whatever its political label, must be an improvement on the KMT. It might have occurred to men less ideologically blinkered than the MCP leadership that the population of a reasonably contented and prosperous country was unlikely to rally enthusiastically to a call to revolution. Even if there were significant numbers of Chinese malcontents or of Chinese who could be brought to heel by intimidation, how could they possibly have arrived at the conclusion that a significant number of Malays would support a movement designed to convert Malaya from its traditional monarchic and Islamic society into a Communist republic dominated by atheist Chinese immigrants? The MCP's strategic assessments were as bizarre as Stalin's confident assessment in 1941 that Hitler would not attack Russia, and Hitler's equally confident assessment that defeating Russia would be as easy as 'pushing down a rotten door'. It might, however, be argued that the MCP had some grounds for their assumption that Britain would not have the stomach for a fight. They had, after all, witnessed the Japanese victory in Malaya and noted Britain's departure from India, Burma (Myanmar), and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the Dutch and French inability to restore their authority in Indonesia and Vietnam. Former CTs, including Chin Peng, have said that the decision to go to war was forced upon the MCP by the defection of Loi Tak, the previous Secretary-General, and his unmasking as a man who had spied in turn for the French, British and Japanese intelligence services. The morale of the Communists had plummeted and drastic action was required to restore it. The MCP were, perhaps, also victims of their own propaganda which proclaimed that, whereas a British Army of 100,000 had been totally defeated by a Japanese invasion force of 30,000, the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) only a few thousand strong had remained in action throughout the war, and so one MPAJA soldier was worth ten Japanese (and by extension many more British soldiers). But, however wrong-headed the MCP may have been in their strategic assessments, they were right in their tactical appreciation that hit and run attacks mounted throughout the Peninsula at a time and place of their own choosing, would be difficult to counter. They fought on the principles laid down by Chairman Mao: never attacking unless they had numerical and tactical advantage, and melting back into the jungle before an effective counter-attack could be mounted. The jungle presented a difficult environment for military operations. During the Japanese occupation of Malaya, Colonel Tsuji of the Japanese Army recorded his dim view of the jungle: "The men covered in leeches and everywhere venomous snakes ready to strike. During the day an inferno of heat and at night the men were chilled to the bone." The jungle had provided the British Special Forces and their temporary allies, the MPAJA, with an excellent base for guerrilla operations and now, once again, it was providing the Chinese Communists with an excellent guerrilla base. I have found no description of life in the jungle written by a Communist Terrorist (CT); but Colonel Spencer Chapman (who commanded Force 136 in Malaya during the war) gives a fascinating account of life in a CT jungle camp, which adds a dimension to the descriptions in the following. stories of attacks on CT camps. The drill, leadership and efficiency of the Communists varied tremendously. At the extreme end of the scale were the ruthless and efficient professionals of the 'traitor killing' camps, highly trained and well-armed, and tasked to eliminate anyone who was suspected of supplying intelligence to the enemy.

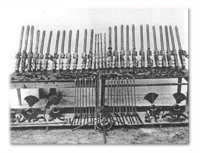

By 1948 the CTs had constructed large, semi-permanent, jungle camps, well-camouflaged, and only approachable along cleverly designed tracks, which were skilfully booby-trapped and guarded by sentries. With six years' experience behind them, many of the CTs were experts in jungle warfare and their jungle craft was often superb. Colonel Spencer Chapman called his book The Jungle is Neutral, but that neutrality gave advantages to those who understood the jungle and were acclimatised to it. In 1948 the CTs were jungle-trained and acclimatised: the Security Forces (SF) were not. Most of the CT armoury consisted of weapons and ammunition that had been air-dropped in generous quantities to Force 136 in the last months of the war. The MPAJA had gone through the motions of handing in some weapons while, in fact, caching most of their military stores for future use. The CTs had absorbed all too well what their British officers had taught them about the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the aborigines in order to have their help for Intelligence and logistic support. The CTs had already set up a group known as ASAL for this purpose: while the SF had to start from scratch to build up their relationship with the Orang Asli (the original people). But probably the CTs greatest advantage over the SF was their freedom to choose target, place and time for their attacks. So in 1948 the CTs had a field day and the SF, particularly the police, suffered heavy casualties. At the beginning of the Emergency there were several thousand CTs under arms in the jungle. Against this force, many of them with jungle warfare experience, the police had only about 8,000 men, who had not been trained as a paramilitary force. The army mustered many thousands more but they too were not trained for jungle warfare. In these circumstances it says a lot for the grit and determination of all the youngsters serving in the police and army that they managed to hold the line. Before the Emergency the senior echelons of government, although frequently meeting to discuss 'the threat', had never clearly identified a threat of imminent armed insurrection. Many commentators have cited 'failure of intelligence' as a prime cause of the government's difficulties. But the documents available suggest that the faults were, by no means, all on the side of the intelligence professionals. The collectors and assessors of intelligence failed to produce a clear picture of the nature of the threat. But their customers the senior officials and military chiefs, contributed to the problem. They grumbled loudly but took no steps to cure the weaknesses of the intelligence machine. In any case, it is nonsense to charge the intelligence community with failure to uncover the Communist plan for insurrection, since in June 1948 the details of the plan had yet to be agreed by the Central Committee of the MCP. The increasing violence that led the government to declare 'war' was the work of rank and file CTs who had jumped the gun. The following report by a group of former senior MCP cadres, quoted by Dato Seri Yuan, makes this point clear. The original plan of the Central Committee was to have ample time for its preparations before launching the armed struggle. It was triggered off prematurely by the inflated psychology of increased resistance it had stimulated in the working masses against the authorities as part of these preparations. Above all the accompanying over excessive emotions of anger and violence which had built up in a number of their cadres who had knowledge of an impending armed struggle, rendered them less willing to tolerate suppressive legal measures imposed and disruptive action by the government. Once issued with weapons they ignored Central Committee instructions. Although they did not attack government forces they went for European planters, police agents and running dogs. The police were at the centre of the war. They had to travel on country roads throughout Malaya in constant danger of ambush and without benefit of armoured vehicles. They and their men suffered heavy casualties as they went about their duties. In December 1955 Tengku Abdul Rahman, Chief Minister of the newly elected Alliance Government and Head of the United Malay National Organisation (UMNO), accompanied by Sir Tan Chenglock, President of the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) and David Marshall, Chief Minister of Singapore, went to Baling to meet Chin Peng in the hope of persuading the Communists to give up the armed struggle. But Chin Peng refused the amnesty terms, insisting that the MCP must be allowed to operate as a legal party, and stalked back into the jungle. Although more and more CTs were surrendering and collaborating with the police, the MCP leadership remained obdurate and a year after Merdeka they were still at war, although by now their army had been reduced to less than one thousand, more than half of whom were lurking in Thailand. The Emergency did not end officially until 1960. The core of this book is the memories of the youngsters of many races, usually plunged in at the deep end with minimal training. It was these Subalterns, Assistant Superintendents of Police, Inspectors, and Police Lieutenants who held the fort in the countryside in the darkest days, and moved rapidly and successfully onto the offensive. The morale of the Subalterns and their men remained high despite the dangers and discomforts of their lives. | ||||||||

| No Surrender | ||||||||

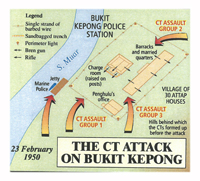

Gallant Last Stand at Bukit Kepong This is the story of how thirteen Malay policemen, supported magnificently by their wives, made a stand against overwhelming odds holding the enemy off for several hours and how, finally, the exasperated CTs showed their usual barbarity and threw men, women and children, some still alive, into the burning remains of the police station. JJ, as his friends know him, finished his career as a Senior Assistant Commissioner (SAC). Tun Hanif Omar a former IGP, writing a foreword to JJ's 'The War Years and After', commended the book as an important contribution to the written history of Malaysia. JJ, the local Officer Commanding Police District (OCPD) at the time, tells the story.

Bukit Kepong was a small village in Johore, up the Muar River, and three and a half hours journey by track and river from Pagoh, my OCPD HQ. I had visited the village the day before the onslaught and Sergeant Jamil's last words to me had been, "Don't worry Tuan OCPD" and a Malay proverb, which translates as 'Better white bones than white eyes' or loosely translated means 'Death before dishonour'. Sergeant Jarnil lived up to his words, firing his Bren light machine-gun with great effect until he was killed. The CT assault commenced about 0400 hours; the attacking force of 180 were from the 4th Independent Company of the Malayan and Races Liberation Army (MRLA) and, no doubt, their commanders rallied them with propaganda about liberating the masses and called them soldiers, but terrorism not soldiering was their trade. Enche Ali Mustapha, the Penghulu (headman), was a dynamic leader who had persuaded the people of his area to rally behind the government and many of his men had joined the AP. The police station was a traditional wooden building perched three feet above the ground on concrete stilts. The defences included trenches and sandbags, but the penmeter fence consisted of only one strand of barbed wire. The police family quarters and the Penghulu's office were within the perimeter. Sergeant Jamil had thirteen regular polIce and three APs under his command in the village and three manne polIce manning the boat at the nearby jetty. There was no radio link to Pagoh so the first objective of the CTs was to kill the marine police and destroy their boat in order to cut the river link to Pagoh. On the afternoon of February 22 1950 when I had left for Pagoh, I did not know that the CTs were assembled behind a nearby hilL At 0400 hours the CTs moved forward and prepared for a set piece attack. The plan of attack was in four stages: first deal with the marine police and their boat; second, enter the police station by stealth, silence the sentry and capture the police constables (PCs); third, raise the Communist flag and declare the village a 'liberated area'; fourth, attack the police on the flanks so as to guard against a counter attack by the APs guarding the Penghulu's office. The assault squads began to move forward at 0550 hours but were spotted and, when they failed to respond to challenge, the police sentries opened fire with their shotguns and killed two of the attacking force. The police then took up their defensive positions and the battle started in earnest: it lasted for about four hours until everyone in the defending force had been killed or seriously wounded. The small defending force, despite the odds against them, kept up an effective fire and their wives picked up their rifles and continued to fire when their husbands were no longer able to use their weapons. After several hours a Malay CT called on the police to surrender. When some of the women and their children came out of their quarters they were ordered to go back and persuade their husbands to give up the battle. The sergeant and his men shouted their defiance, but eventually the CTs. prevailed by sheer weight of numbers and the police were forced out of the police station when the CTs set it alight with petrol bombs. Those who managed to escape from the burning building were shot and any wounded were thrown into the flames by the triumphant CTs. One marine policeman, who could have escaped, remained with his boat until he too was killed.

As soon as news of the attack reached Pagoh I set off immediately through the jungle with a rescue force of ten men from the jungle squad and some Seaforth Highlanders, and forced marched to the village by. The scene was horrible; a burning police station, dead policemen everywhere, women and children who had survived were wailing and crying. Fortunately, the discipline of the police was such that any thoughts of reprisals against the local Chinese were quickly overcome. This was as gallant a defence as any in history; the garrison had many opportunities to surrender, and the fact that their families were under fire as well added to their plight. In 1976 the lOP visited Bukit Kepong to preside over a ceremony of remembrance and rearrangement of the gravestones and the burial ground of the heroes of Bukit Kepong. The following is a verbatim statement by a CT who took part in the Bukit Kepong attack. The statement reflects the magnificent heroism of the Malay policemen and their families, the brutality of the CTs and the overwhelming odds against the defence. Statement by CUING MOl CUAI aged 43 years Member of the 4th Independent Company MRLA I was a member of the gang that attacked Bukit Kepong Police Station on 23 February 1950. We chose this station as the target because it was isolated, it had no radio contact with other stations and we wanted to strengthen our prestige in that area. There were 200 men in our gang and we knew that only twenty Malays manned the police station. We encircled the station at 0400 hours. We chose that time because we thought the sentries would be asleep. At exactly 0430 hours the bugle sounded and our attack started. We fired on the station from all sides. We immediately received a heavy barrage of return fire. I was in the party attacking the front of the station and I could see the policemen taking defensive positions. They had divided into two sections. One section manned the defences under the station using two Bren guns and the other section manned defence posts in the charge room above. A few men, I don't know how many, defended the married quarters at the rear of the station. Most of our armament was automatic weapons but some of us were armed with rifles and grenades. The greatest resistance to our attack was coming from underneath the station where the Bren guns were. We concentrated our attack there and, after about one hour, it was silenced. We then received orders to charge the front of the station. This we did with fixed bayonets but the gunfire was so intense that we withdrew to reform for another attack. In that attack we lost two killed and several wounded. We then called on the police to surrender promising them no harm if they did so. They refused and increased their resistance. In the meantime, some of my comrades had been attempting to break in at the rear of the police compound but they had been met by stiff resistance and suffered several casualties. When daylight came we were able to see the damage better. I could see dead policemen lying under the station. The one in charge, Sergeant Jamil, was slumped over one of the Bren guns. We received orders to charge and we did so, time after time, but we were still unsuccessful, so we withdrew and again called on the station to surrender but again they refused. Our leader was getting impatient and so he ordered us to attack the married quarters, which was the weakest part of the defence. They could not defend that properly and we were able to break through the defences. One of the police wives tried to run to the station but my comrades caught her. They asked her to walk to the station and call on the men to surrender. She refused and she told my comrades that there were only two people left alive in the married quarters, a policeman's wife and daughter. My comrades shot the wife they had caught and called upon the one in the quarters to surrender. She refused and shouted that both she and her daughter preferred to die. So my comrades set fire to the married quarters and burnt both of them alive. Then they threw the body of the other wife into the blazing building. There was a boat moored at the rear of the station and a marine policeman defended that until he was killed. He could have escaped but didn't. We had got into the compound and now charged both front and rear. We got within grenade range and threw several grenades into the charge room. Then my comrades set fire to the rear of the station. A group of several policemen came charging out of the front firing their weapons. Some of them had their clothes on fire. their wives also came out and, as we shot their husbands, the wives picked up their guns and continued to fire at us. We were able to shoot them all and throw them into the burning building. They were not all dead when they were thrown. Just as we were leaving, we found a small boy under a bunker and my comrades threw him into the fire as well. The attack took us five hours. The Defence of Kea Farm Dato Seri fuan fuet Leng finished his distinguished career as a SAC, but his book 'Operation Ginger' describes his view of the Emergency when he was a Special Branch Officer (SBO) in Perak. Tun Hanif Omar's foreword to the book, commending the author and his contribution to history, remarks: "Cooperation amongst the government forces did not come naturally, given the propensity for one-upmanship - but there was an unconditional acceptance of the police role and in particular SE which never let them down. " "In preparation for the Baling Talks (1955), the MCP made a major effort to demoralise the Home Guard (HG) in an effort to strengthen their negotiating position. The Cf attack on Kea Farm was part of this effort. The gallant SF resistance ranks with the Last Stand at Bukit Kepong in the great tradition of the Malay Mata Mata's courage and determination in the face of vastly superior numbers and deserves a lasting memorial. In June 1955 the MCP, after a Central Committee decision, made overtures to the government for peace talks on an assumed basis of equality. This was contrary to the realities of the security situation and the strong position held by a new and elected Malayan Government, which had pledged to offer an amnesty to the Communists in order to end the shooting war. As a prelude to the on-coming talks and to strengthen their hand, a number of major incidents were carried out, notably in Johore and Perak. In Perak, Kea Farm New Village, five miles from Tanah Rata in the Cameron Highlands, was attacked and occupied for two hours on the night of 31 sI October 1955 by about 100 terrorists. CTs were mainly from 27th Section and 25129 Section of 31 sI Independent Platoon who normally operated in 10th MCP and 7th MCP Districts respectively. Overpowering the local HG command post a terrorist party, guided by the HG platoon commander (under duress), proceeded to an identified house where they murdered HG Chow Yip Shin, a vegetable farmer aged 41. Chow was stabbed twice in his throat and again in the chest. Other terrorists collected 35 HG weapons and 612 rounds of ammunition in a house-to-house search, and raided the village shops. All this occurred without a shot being fired and then another group of terrorists surrounded the police station and penetrated into the compound. They opened fire when the police commanded by a corporal refused to surrender. The police returned fire and one constable, ignoring the terrorist fire, dashed out of the station to start the standby generator outside in order to operate wireless equipment, as electricity and telephone lines had been cut off by the CTs, and was captured. Soon after Constable Omar bin Mat, shooting from under the elevated police station, was hit and died. The terrorists reached the station building and splashing kerosene oil under the building, attempted to set it on fire but without much success due to the rain earlier. However, Constable Abu bin Sipes, who with PC Omar had been engaging the terrorists from a trench, had to make a run from the heat of the flames and was also captured. The three remaining police personnel withdrew from the bullet-ridden station to a bund behind which they continued to engage the terrorists. One of them, PC Osman bin Kassim, managed to sneak away in the dark and ran two miles to the nearest Gurkha camp to gi ve the alarm. When he returned, the terrorists had already withdrawn, regrouped and moved off with their spoils. Government reaction to the incident was fast. The previous 'Shout before your shoot,' order to SFs in connection with the amnesty offer was rescinded, and a number of the 186 'safe areas' in the country provided for terrorists intending to surrender were also abolished. The Kea Farm follow-up found the Cfs camp at the edge of the local safe area and also confirmed that terrorists had actually passed through the safe area in order to reach the village." A George Medal for a SC Three Special Constables (SCs) were awarded medals for gallantry in an action in Sungei (river) Siput, which spoke volumes for their courage and for their training and, indeed, marksmanship. Wan Amran was awarded a George Medal (GM) and his two companion SCs were awarded Colonial Police Medals (CPM) for gallantry. This stirring account is a reminder of how much brave work was done by SCs, APs and even HGs, all temporary not regular members of the SF. Wan Amran's laconic description of the incident is as follows:- I was one of a patrol of eight SCs moving through a rubber estate when we were fired on. The first burst killed four of us and wounded two more. I, Mat Din bin Urnai and Musa bin Kamis, threw ourselves down and lay quiet on the ground while the firing continued for about ten minutes. Then the bandits shouted, "Those of you who are alive surrender and we will not harm you." We did not stir. A minute later I heard a rustling sound to the rear, and turning round saw a bandit coming towards me. He fired at me and a shot grazed my shoulder. I fired back and killed him. The bandits then opened fire again and all three of us returned fire. Next, two bandits left their positions, which had sandbags around them, and tried to capture the Bren gun off our leading man who had just been killed. I fired at the first man and killed him. The second bandit ran away. Then two bandits emerged on the right and moved towards two of our wounded comrades in order to seize their weapons. I fired again and one bandit fell dead. All the time Musa and Mat Din gave me covering fire from their positions in front and behind me. Musa had fired 50 rounds, Mat Din 70 and I 20 by the time the bandits retreated. The SCs had stood off four assaults by a CT ambush party numbering over 30 who were armed with Brens, carbines, Stens and rifles. | ||||||||

| The Recruits | ||||||||

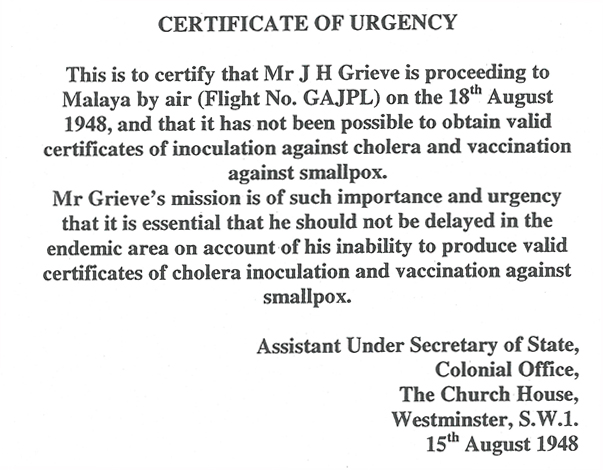

To Malaya by Constellation The late 'Snodgrass', whom I had the pleasure of knowing over many years, was a most distinguished officer who rose to the top of the Colonial Police. Since he chose to use a pen name when he was alive, I have maintained his anonymity. Many of his old colleagues will recognise his ebullient character and sense of humour. The Colonial OffIce telegram was curt but clear. If you are still interested in joining the RMP report to Hounslow Barracks, London, next Sunday. Next Sunday was 12th September 1948. My previous correspondence with the Secretary of State for the Colonies had been in 1942 when as a schoolboy I had attended an address by a former pupil on his career in the Malayan Straits Settlement Police, from which he retired as the Chief Police Officer (CPO) of Singapore. He had impressed my schoolboy mind so much so that, there and then, I penned a letter to the Secretary of State saying that I would much appreciate an appointment in the RMP when I left school. I received a most courteous reply, "Sir!" it said (I was suitably impressed), "The Secretary of State has directed me to inform you that your request has been noted. Unfortunately, Malaya is temporarily under the administration of the Japanese Government, but when this situation has been rectifIed, we will consider your application." I was impressed again when the squiggle at the foot of the letter begged to remain my most obedient servant. The telegram was a surprise. Some five years after the polite official letter to the schoolboy, I had called at the Colonial Office during my National Service demobilisation leave, only to be stopped at the doorway by the commissionaire and informed, in no uncertain terms, that there was a waiting list of some six years for appointment to the RMP. And now, a couple of months later, here was this hasty communication which didn't even beg to be my servant _ obedient or otherwise. I did not realise until later that a State of Emergency had been declared in the Federation of Malaya. The whole country was in turmoil as guerrilla terrorists of the MCP were in open revolt and wreaking mayhem and murder, and the high commissioner had been killed in an aircraft accident. No wonder reinforcements were being sought. Part of Hounslow Barracks had been loaned to the Colonial Office as transit accommodation for police reinforcements being flown out to the troubled territory. "Gentlemen, thank you for turning up so promptly," said the dapper civil servant in the gloomy, colourless assembly room in the old Victorian barracks. "We haven't much time to give you information as you are flying out tomorrow at dawn by BOAC from Heathrow. I am assured that you will be fully briefed when you land in Singapore." After a desperately uncomfortable night (a straw palliasse on a metal strip bed does not induce sleep), at dawn next morning it was somewhat of a relief to board an army truck for the airport. All of us had been issued with travel vouchers, which addressed each one as "Sergeant". "Mighty quick promotion," one of the travellers observed, "Maybe we'll be inspectors before we arrive." A BOAC official mustered us into one of the sheds, which had over its door a pretentious sign - DEPARTURE LOUNGE. He announced that we would be boarding a chartered Constellation aircraft 'shortly' and, in the meantime, we should make ourselves comfortable. The only comforts that could be seen were some metal folding chairs and a couple of backless benches. Two tedious hours later, after several paper cups of weak coffee obtained from an ancient machine, which bore the faded letters NAAFI, we were directed to pick up our luggage and move out to our plane. "Oh! By the way," said a uniformed official, "I suppose you all have passports?" Some of us hadn't but with boisterous shouts of "Of Course!" we were led on to the tarmac and a half-mile trudge to an aircraft that obviously had many air miles under its fuselage. One after the other, three of the piston engines roared into life causing the rivets in the cabin fuselage to quiver and rattle. The propeller of the last engine churned and groaned but no way was the engine going to fire. All back to the Departure Lounge. Three hours later we were back on board. We held our breath as the fourth propeller started to rotate. This time, the engine not only did fire- it went on fire! Back to Hounslow Barracks and another spartan night with the military. At least the meals were plentiful. Another dawn start in pouring rain. Whilst we were being marshalled, it was discovered that two of our number were missing. Much confabulation concluded that yesterday's experience had persuaded the two absentees that life in the RMP was not for them. Or could it have been that the form of transport to Singapore had changed their minds? With revving engines and clattering rivets, we lumbered on to the runway and, with a deafening combination of full power piston engines and cheers from the relieved passengers, the Constellation took off, climbed through the rain clouds and set its nose towards the rising sun." By Deckchair to Malaya Gus Fletcher moved from the RMP into diplomacy where his outstanding gifts as a linguist and human relations skills continued to stand him in excellent stead. Gus told me that after the war, which he missed by a whisker, a glamorous poster attracted him on his local railway station, showing smart officers on horses and motorcycles, inviting recruits to join the Palestine Police Force. When the British Mandate ended he was still looking for adventure. In the summer of 1948 I was casting about as to what to do next following my premature return to the UK from Palestine, the police force there having been disbanded. I saw in a Sunday newspaper that Malaya needed five hundred exPalestine policemen to deal with a 'Communist uprising'. I was not entirely sure where Malaya was, nor what constituted a Communist uprising, but wrote to the Crown Agents for the Colonies for further information. In short order I found myself in Hounslow Barracks. There were about 40 of us, all ex-Palestine police, our ages ranging from old men of 40 to young squirts like me, 19 years old. After a couple of nights in barracks we climbed into our aircraft. Where the seats had been were two strips of canvas for bottoms, with two more strips for backs. These were in pairs, and so cunningly designed that when you sat down your neighbour soared upwards; when he got up you sank towards the floor. This was at first mildly diverting, but after fifty-odd hours much of the fun had gone out of it. A few rows in front of me was Col W N Gray, our erstwhile IGP in Palestine who was in black jacket, pinstripe trousers, waistcoat and bowler hat. As our aluminium tube lumbered eastwards to ever hotter regions, and as we climbed back after each landing into an increasingly oven-like atmosphere, our Commissioner divested himself of his outer garments one by one; eventually - I think by the time we were in Basra - being reduced to trousers and vest, with his braces over his vest. For reasons unknown, however (and it was the subject of much speculation), he kept his bowler on in the aircraft. But each time we landed, when he led the way off the plane, he was once more the picture of sartorial correctness. And onwards, ever onwards, we flew, our yo-yoing canvas seat straps now, it felt, leaving their imprints permanently on our posteriors. And, blessed relief, Singapore finally slid under our wings and we were released from our fifty-hour torment. It was late (I think about 01000 hours) and the warm, damp air enveloped us as we trudged our way to transport that took us to the Nee Soon Barracks where we were told that we could sleep until 0600 hours. As it was 0300 hours by then this did not seem a generous offer. By 0800 hours we were each in possession of Sten guns, three magazines, ninety rounds of ammunition, ex-Indian Army khaki shirts, shorts, slacks, a camp bed of astounding complexity and other impedimenta. Then on to the day train to KL. I remember scarcely anything of that steamy, rattling journey. Like the rest, I dozed through the long, hot, sticky day. On the platform at KL we found our commissioner awaiting us. Consulting his notes, he told us we were all going to the State of Pahang, where CT attacks were widespread and where general mayhem prevailed. We would be billeted upon rubber estate managers in pairs - an older man with a younger one. I don't remember how we paired off; it was rather like waiting on the playing field to be picked by opposing team captains. My 'old' partner was aged 25 or so and had served through the recent war. Gray wished us well and hoped to visit us on our rubber estates before too long. A Planter is 'Volunteered' to be a Police Officer J A L Carter was born in Malaya, son of a rubber planter, and served in the Navy in World War Il. After taking a degree in tropical agriculture, he had barely started work as an Assistant Manager on an estate in Johore when the Emergency began. "On 3 July 1948 I was sent for by 'Bottle' Hargreaves, the Officer Supervising Police Circle (OSPC) in Johore Bahru, and was told that he intended to 'conscript' me into the police as.I had proficiency in small arms and that I would be 'employed' VOLUNTARILY (!) to train SCs.

My protest that I had just fought one war and was now a peace-loving civilian was dismissed; but, as a sop to my feelings, I was told that I would carry the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP), without emolument! That cheered me up a bit and I went to work on some super young Malays from surrounding kampongs (villages), training them to defend rubber plantations. The following year my planting job took me up country to Paloh. Leonard Knight, who at that time was CPO Johore, sent for me. The MU had become the Federation of Malaya; I had lost my commission but, if I wished to continue to serve, I could do so as an Inspector. I cheerfully accepted! Amongst the thousands of men who served as Colonial Police Officers over the years, I am, as far as I know, the only officer who was 'bust' because of a change in the constitution and name of the land in which he not only lived, but had been born. I enjoyed my service with the RMP, although nothing very spectacular happened during my time. I was attacked at night m my bungalow a couple of times, and had the sad duty of picking up the bodies of both A H Girdler and G B Folliott OSPC Kluang, when they were ambushed in April 1950 on the Yong Peng to Paloh Road." From Banker to Jungle Wallah Alastair's pieces are a reminder of how, between jungle patrols and police duties, the subalterns still found time to play. When did it all start? I thought I should settle for a steady job and secured a position as a management trainee with the British Bank of Iran and the Middle East. After eighteen months I felt this was not really my cup of tea and cast about for something more active. I discovered that the Colonial Office was looking for people to join the Colonial Police. I applied and got a formidable application form that required various references including a Certificate of Equitation. I had to attend two interviews after which I was told that my application had been successful and that, because of my previous maritime experience, I was being considered for appointment to British Honduras Police Marine Division, but I would first of all have to pass a police training course. Then I was told that the British Honduras posting was cancelled and I would be considered for Malaya. I was then instructed to report to the Colonial Office before joining the trainees who would be going to No.3 District Police Training Centre in Staffordshire. The London Resident Director of the Bank gave me an exit interview: I thanked him for my training but added that I felt I was not cut out for a banking career. He agreed. The training course was the UK Constable basic training lasting for thirteen weeks after which we 'Colonials' attended the Metropolitan Police Training Centre at Hendon. We learnt evidence, law, and procedures, and received instruction at the Detective Training School. Finally we were attached to the Metropolitan Police, a County Force and a Borough Force. From Heathrow we flew to Rangoon, the scheduled night stop. We decided to go for a walk after dinner. Somehow we became involved in a Burmese wedding, which was quite a party. Eventually we found ourselves back at the Strand Hotel and so to bed. We seemed no sooner to have gone to sleep when there was a banging on our door and someone telling us that the bus to the airport was waiting. So we arrived at Singapore and, finally, the great day came for our journey to KL. We were issued with a.38 pistol and six rounds just in case of trouble on the train. We noted that our fellow passengers were carrying all sorts of firearms, which seemed more serious than our revolvers. We finally arrived at Police HQ and were taken to a one-month course at Fraser's Hill, to introduce us to the Malay language, local law and criminal procedure. On this course there was an officer from a police jungle company, and I was curious to learn how this fitted in. Our training course in the UK naturally had made no mention of such matters. I was advised to ask Police HQ. The answer to my query was, "Under no circumstances will Mr Cochrane-Dyet be posted to a jungle company in the first instance." On the completion of the course a telephone call instructed me to report to Police HQ jungle companies, where I was told I was posted to No.16 Jungle Company at Titi-Gantong, Grik." Dato Pilus Joins Up Dato Pilus was born in Kampong Sungkak near Kuala Pilis in 1917. His autobiography is written with a light touch, but in it his seriousness of purpose, devotion to duty, patriotism and dedication shine forth: and so too his devotion to and pride in his family. However, he clearly was not a 'Yes' man. He joined the police in 1935, retired when the Japanese occupied Malaya but rejoined the police, taking the view that his duty was to maintain law and order. His book reflects the mutual respect and affection that, for the most part, existed between the Orang Puteh and their Asian colleagues. Sadly, this happy relationship is seldom reflected in post-colonial commentaries: it is not fashionable to record the truth in these matters. We did respect each other, although of course the rules of the day gave the top jobs to the colonial visitors. Dato Mohammed Pilus is almost certainly the only Royal Malayan Police Officer to have been ambushed by both the MPAJA and the MRLA.

Dato Mohammed Pilus served in the RMP from 1935 to 1971, rising from constable to SAC. Tun Hanif applauds his book, 'A Policeman's Story', and describes it as 'An important contribution to Malayan history.'" I appeared before the CPO, a slightly portly Englishman: I lIked him instinctively. He told me to report to Bluff Road "Any time you wish," smiled, and wished me good luck. I travelled to KL by train: so far Allah had guided every step I had made, and on New Year's Day I met the redoubtable Commandant of the Depot, who produced the recruitment forms and on January 4 I reported to the Depot. The day was full: Reveille before 0600 hours, drills and parades until. 0900 hours, curry lunch and classroom work, then more parade ground drill until we became expert. I feel a glow of pride whenever I see our police team parading overseas. Once deductions had been made, the pay was very small. It was a tough regime and some recruits from better off families bailed out, paying three months salary to discharge their obligations. When, on graduation I was posted. to Perak, the Commandant briefed me that the Perak people were proud and unpredictable: they did not take kindly to police authority and had once bundled a policeman into a sack and thrown him into the river. I duly reported for duty to Parit, part of the Kuala Kangsar police District. Sergeant Major Ismail was Officer in Charge (OC) Station. Raw as I was, I could not help feeling that there was not much active police work to be done in Parit. The only theft was of a bicycle, and that case was passed to the corporal." | ||||||||

| In At The Deep End | ||||||||

New Boy in Kuala Lipis David, who was brought up in Penang until the Japanese war, was commissioned into the Northamptonshire Regiment and served in Trieste. We have never met but we have one common experience: we both suffered at Officer Cadet Training Unit (OCTU) under the formidable but most admirable Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) Copp of the Coldstream Guards. David's expertise as a marksman and weapons expert stood him in good stead when he joined the police in 1952 as an ASP. He has been a most enthusiastic supporter of Operation Sharp End. David Brent's description of the somewhat daunting range of duties, which he was required to carry out as a newly minted police officer, will perhaps surprise Britons of the 21" Century. The list represents the typical challenges faced by youngsters setting off in their first posting in the Colonial Service. We arrived young, probably with only military experience behind us, and almost certainly without first-hand knowledge of the territory. Even without a full-scale Emergency to cope with, the responsibility was considerable. But, like military service, it was an experience that stood the survivors in good stead for life. We learnt on the job, supported generously by our Malayan colleagues. And the job usually gave a great deal of what, in modern management speak, is known as 'job satisfaction', which we all remember with pleasure fifty years on. My first posting in Malaya was to Kuala Lipis under Wallace Kinloch, the OCPD, a broad-accented Scotsman and fIne officer, who had been with the Scots Guards and then the Hong Kong Police at the time of the Japanese attack. Kuala Lipis was one of the largest police districts in Malaya, almost geographically dead centre of the country; it was the administrative town of Pahang and housed all the government head offices.

Wallace Kinloch acquired a tiger cub, which he kept at his home near the railway track on the edge of the township. It was quite a placid and friendly animal but I understand that it made a mess of anything it could get hold of and chew, which included table and chair legs, shoes and carpets. As it grew bigger and more destructive and less tractable, Wallace found a home for it at the Edinburgh Zoo. I relished my first experiences in crime investigations, mUltiple administrative duties, Chandu raids, road blocks and searches, jungle patrols, police station inspections and pay days, setting up beat patrol systems, liaison with SB for special operations, liaison with military units, ceremonial parades, night duty offIcer, vehicle and boat maintenance, up-river journeys by boat to far-flung police stations and posts, inspections of rubber estate security systems and personnel, liaison with rubber estate managers, liaison with Penghulus, Ketua Kampongs (headmen of the kampongs), personnel management, and so on. A Cadet ASP's First Patrol In late 1948 I resigned my commission in the Royal Tank Regiment and was appointed to Malaya as a police cadet. I soon found myself in the hurly-burly of Campbell Road Pohce Station as Assistant OCPD KL North. Tim Hatton, exGurkhas, was OCPD. He spent most of his time running a ferocious looking jungle squad and hunting for 'bandits' (as we then called the CTs) in the jungles north of KL and left the policing side of things to me. This was quite a lot for an inexperienced twenty-one year old to take on, but I was quite happy to do it and learn as much as I could about being a policeman. Tim's jungle squad had to be seen to be believed, It consisted of about thirty Malay and Indian policemen dressed in jungle green and armed to the teeth, brandishing rifles, Stens and Brens with hand grenades stuck ID theIT belts. Every now and then one of his section leaders, a large and imposing Sikh sergeant, would march into the offIce which. Tim and I shared, give a butt salute on his Sten gun, receIve instructions from Tim, shout "Sahib!" and march out. Then chaos ensued as Tim and the jungle squad poured into their vehicles that went roaring out of the station compound. "Would you like to go on an ambush?" asked Tim one day. Enthused by his squad's arrivals and departures I saId, of course I would. But then I learned that I would not be going with the jungle squad but in charge of a party of Chinese detectives. So, at 1600 hours on a hot, humid afternoon we got into a black, wooden-sided police truck and headed north towards the Batu Caves through what seemed like an endless series of Malay kampongs standing amidst coconut trees. Lorries pulled over to let us pass, their cargo giving us those varied smells that added a touch of mystery and excitement to the country. How clearly one recalls them: durian (fruit with a penetrating smell); Chinese cooking; the humid air; and in this case the unmistakable whiff of tightly packed sheets of rubber. We passed a tin dredge, which looked like some metal monster floating in the lake it had created, then came to the vast, towering exotic limestone rocky outcrop of Batu Caves; two miles round, five hundred feet high and covered in jungle growth that was home to birds and monkeys. In the caves on its northern face a small gang of CTs had their base. their role was to collect food from the Chinese squatters who lived round the edge of the rock and hills and take it to the gangs deep in the jungle. Our role was to ambush one of their jungle supply routes. We drove along a narrow bumpy track with high grass on either side, to the northern end of the outcrop. It was getting dark by now. The occupants of the occasional squatter hut peered at us then, realising who we were, withdrew inside their homes. Ducks quacked, dogs barked and open latrines stank. We passed through a small village and came to the edge of a rice field where we stopped. The ambush party got out of the truck and I followed. Imagine now a bunch of squat Chinese detectives dressed in an assortment of civilian clothes, many wearing hats of different shapes, grinning at me with gold-filled teeth. This was my ambush party. They were armed with a variety of weapons and nonchalantly brandished their pistols, submachine- guns and rifles. I only hoped they knew how to use them because, young and inexperienced as I was, my life was in their hands. In the gathering darkness we set out at a brisk pace along the side of the rice.field. It was flooded and I kept slipping off the edge into the water and floundering back out to find my feet again, trying to keep up with my more agile companions. Rice field followed rice field then, in the distance, loomed the edge of the jungle. It was quite dark now but there was the light of a full moon by which we followed a path leading into the ominous blackness ahead. With the moonlight glinting on the path, together with the shadows of the trees and undergrowth, this was my introduction to the jungle that I was to get to know so well. The path rose upward along the side of a ridge, crossed over the top and wound downwards again. We were still walking at a very rapid pace and it was much darker now as the moonlight failed to penetrate the canopy of trees above. I stumbled along following the figure of the detective in front of me, and keeping on the path with great difficulty. Not a word was said by any of my companions, all was deathly silence, not a sound coming from the gloom on either side of me. After we had been walking for about an hour, we suddenly stopped and the detectives disappeared into the undergrowth to the right of the path. One remained with me and explained in Malay that this was the best place for the ambush. I followed him off the path and up the side of a steep hill, near the top of which we crouched down among some bushes. The jungle trees had slightly thinned here and enough moonlight penetrated to light up the area around us. At the bottom of the hill was the path bending away to the left so that we were looking directly along it. Visibility was about twenty yards, after which it was darkness again. I looked around and saw other shadowy figures squatting in the undergrowth gazing, like me, towards the path. We seemed to sit in the darkness for ages. All was silent except for the occasional cracking of a twig as one or other of my companions moved slightly. I had time to think about the situation: I was miles away from anywhere, in the middle of the Malayan jungle with no precise idea of my location, sitting among a bunch of Chinese detectives about whom I knew very little. Suppose I got lost, how would I get back to civilisation? Suddenly I was woken from my thoughts, as all hell broke loose on either side of me. My companions started firing their various weapons in the direction of the path. The flashes of their guns lit the darkness and bullets whistled over my head: it was getting rather dangerous, especially as the firing was uncontrolled. I strained my eyes but could see nothing at all on the path. What were they shooting at? I decided to take control and in my excitement shouted, "Stop shooting you silly bastards! ' This seemed to have a magical effect. The shooting finished and I could now see shadowy fIgures standing up in the Jungle around me and waving their firearms in the direction of the path. I crept forward with one of my companions. Suddenly, he jumped onto the path and triumphantly held aloft a battered old trilby hat. The other detectives emerged from the undergrowth and gathered on the path. I managed to find out from their excited chatter what had happened. Three armed men had been seen creeping stealthily along the path. Someone had fired too soon and they had dIsappeared. This, I learned, was the way it was in the jungle: contacts and then, perhaps, nothing. Tim was there to greet us on our return. "Bad luck you mIssed them," he said. "Quite honestly, I didn't see a bloody thing," I replied. Apprentice Patrol Leader CID Michael, although commissioned into the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, was too tall and was transferred to the Royal Engineers after service in Sudan, Egypt and Greece. After demobilisation and a spell as a Territorial Officer in the Artillery, Michael Engel set off to join the RMP. When we arrived in Singapore we were invited to join the local Force. Shock! Horror! We were keen as mustard, some might say pathologically stupid, and we certainly had not come all this way to enjoy the bright lights of Singapore. So we agreed to draw lots and two dispirited comrades were left behind to their fate in Singapore. No doubt they were destined to enjoy a long career and steady promotion. Opening my sealed orders on my second day in Malaya, I discovered that I was to be known as a Patrol Leader Criminal Investigation Department. I arrived in Sungei Patani and reported to the OC CID, Bill Luscombe from Sydney, Australia: a man of few words, mostly pejorative. He introduced me to a group of fIerce looking Chinese and said, "These are your men." Later, it transpired that some of tllem were police detectives, while others were former members of the wartime MPAJA. The next day I was invited to go into the depths of darkest Kedah in order to look for what had been described to me as up to 250 armed CTs. The 8th Regiment MRLA was on the move with the intention of creating mayhem in South Kedah and North Perak. After only two days in the country I was unable to speak Malay, still less Tamil or any Chinese language, and anticipated a communications problem. I was relieved to hear that two experienced European sergeants would accompany me. Both were ex-Palestine policemen. We arrived on the south bank of the Sungei Muda, which was wide and fast flowing. I held an '0 Group' with the two sergeants and sent one upstream with about five men to select a suitable ambush position, and the other downstream with a similar number of men. I took the central position with five men. Each of us was equipped with a US .300 carbine (useless) and a Browning 9mm pistol (better). We also had three Bren guns (excellent), one in each group. Apart from shouting we had no means of communication. I had seen all those films about the war in Burma and the Pacific and so I thought that I knew instinctively what had to be done. I can remember my order quite clearly, even after all these years. "Hold your fire until their rubber boats reach the middle of the river. Aim for the boats and we will take prisoners." The two sergeants looked at me in silence for some minutes. "These guys use bamboo rafts," said one sergeant quietly. In the end there was no contact with the enemy. We packed up and got back to Sungei Patani, evil-smelling, tired, hungry and knackered, I reported to Bill Luscombe and told him that we had not seen any CTs; he looked up and said, "I hope you are better at tennis." On another occasion I was on a fighting patrol with the same two European sergeants. We were wandering around in Central Kedah looking for a CT camp. We were a long way from human habitation when suddenly a Chinese boy came dashing along the track towards us. One of the sergeants grabbed the boy by the scruff of the neck and in one swift movement drew his pistol and held it against the boy's head. Turning to me he screamed, "Shall I shoot the ******, Sir?" I ordered him to release the boy and the sergeant, very unhappy with my decision, said that the boy was almost certainly a CT courier. Fifteen minutes later we walked into a well-organised ambush." CT Heads and Other Matters In 1949 a combined police/military operation was mounted in the Gunong Bongsu Forest Reserve on the Kedah/Perak border. The object was to kill or capture all CTs in the area. This was in the early days when people talked about 'cordoning off' large tracts of country, including dense jungle. Three Battalions, two British and one Malay Regiment, constituted the cordon. The killing ground was bombed and strafed by the RAF, shelled by a field battery and subjected to sporadic shelling and machine-gunning by armoured vehicles from a Lancer Regiment. When the dust and smoke settled I found that I was in charge of the one and only police unit instructed to follow up the bombardment. The unit consisted of about fifty men, drawn from different parts of Kedah, mostly Malays, some Sikhs and Punjabi Mussulmen. They had never worked as a team and some of them had never been involved in this type of operation before. We started off and passed through the cordon. After about an hour and still in open country, I spotted mist or smoke rising above the treetops on a hill feature. Some of the men thought it was mist, but I was sure it was smoke from a cooking fire. We made our way towards the hill, the patrol strung out in single file. They were making a hell of a lot of noise, so I ordered a halt. After choosing one of the Malays, a Sikh and a Punjabi Musselman, I told the others to go back towards the start line and wait. The four of us moved forward very slowly and continued uphill, where we found an occupied camp. We shot and killed one CT and recovered a weapon and documents.