|

| Heligoland |

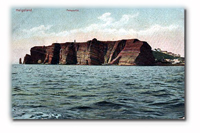

First, the simple question: where is it? Heligoland is a tiny and isolated island of half a square mile (one quarter of the size of Sark) about 40 miles off the coast of Germany in the North Sea. The nearest German port is Hamburg in the estuary of the River Elbe. Heligoland is about 300 miles from Norfolk, the nearest coastline in England. The island is a rock of very old Triassic sandstone which survived the ice ages. It has a habitable plateau with a small town and a good natural harbour, and was once surrounded by miles of sand and marsh which have been swept away over the years by North Sea storms.

Next question: who did it belong to? In the 18th Century it had been alternately owned by Denmark and the German provinces of Schleswig and Holstein, the neck of land linking Germany and Denmark. It was captured by the Royal Navy in 1807 during the Napoleonic Wars to deprive the French navy of a base in the North Sea. It was ceded to Britain by Denmark under the Treaty of Kiel in 1814 and ratified by the Treaty of Paris later that year. At that time the Admiralty considered Heligoland to be too distant and exposed to be a British base and it was never developed as such for the Royal Navy (although it later became an important German naval base). It nevertheless became a British colony administered by the Colonial Office. From 1826 onwards under an enterprising British Governor, the island grew into a spa, popular with well-heeled European visitors for health reasons, and attracted a cosmopolitan group of artists and writers as residents who mingled with the small German-speaking population.

When Britain gained Heligoland in 1814 there had been no opposition from Prussia, the kingdom to which Schleswig-Holstein belonged, and whose coastline was the nearest to Heligoland. Germany was not at that time a unified state which it later became under the leadership of Bismarck, the Minister President of Prussia serving King Wilhelm I. In 1871 Bismarck succeeded in unifying all the German-speaking territories other than Austria under King Wilhelm of Prussia as the first Emperor of Germany, while he himself became the first Chancellor. The British government did nothing to interfere with the process of unification which it viewed as creating a satisfactory balance of power in northern Europe between France, Germany and Russia. Anglo- German relations remained cordial throughout the reign of Emperor Wilhelm I.

The early years of the colony of Heligoland were thus relatively quiet, but German interest and influence in the island grew steadily with the adoption of the new Reichmark as the currency, and trade remained largely with Germany and in German hands. A factor which did much to promote this was the construction of the Kiel canal through Schleswig-Holstein in 1887 linking the German Baltic coast with Prussia's north sea coast and Hamburg. Not only did this promote trade but it also gave the German navy based in the Baltic easy access to the North Sea, which enabled Germany to become a new naval power in Europe. The harbour of Heligoland thus came to be seen as a potential prize to be won from Britain as a base for the German navy; and that is indeed what subsequently happened as a result of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty.

|

| Leaving Heligoland |

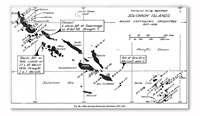

We should now look at the background in Africa to the negotiation of that Treaty, while the "Scramble for Africa" was going on. Germany under Bismarck had become a major player in the scramble, both in East Africa and in South West Africa. In East Africa Britain and Germany had been vying with each other for many years for influence with Sultan Majid of Zanzibar, and in 1886 they started to negotiate with him the right to administer the coast of East Africa. The Sultans had historically claimed sovereignty from Lamu in the north down to Cape Delgado (later part of Portuguese Mozambique) in the south. In 1886 a British-German border commission recognised the Sultan's claim to a ten-mile wide strip all the way up and down that coast. In protracted negotiations with the Sultan, it was eventually agreed that he would cede to the German East Africa Company the right to administer the coast of what later became Tanganyika; and to the British East Africa Company the right to administer the coast north of Tanga which later became Kenya.

|

| German Fortifications |

In 1890 Britain and Germany formalised this agreement with the Heligoland- Zanzibar Treaty. Under the Treaty, Germany also recognised the special relationship which Britain had acquired with the Sultan which led to British Protectorate status for the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba. The Sultan retained sovereignty but accepted an increasing role for British colonial appointments in his administration. The dominant position which Britain had acquired with successive Sultans had resulted to a large extent from the role which the Royal Navy had played from 1822 onwards in the suppression of the Arab slave trade in East Africa. This had followed the outlawing of all British involvement in the Atlantic slave trade in 1807 and the abolition of slavery in all British colonies in 1833. This reputation (plus a bit of gunboat diplomacy) gave Britain a unique leverage which enabled Sir John Kirk, the British Consul in Zanzibar, to persuade Sultan Bargash to sign a treaty in 1873 abolishing the slave trade in his territories.

|

| James Fergusson |

That was the background in Africa to the negotiation of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty. It was of course the Germans who were the "demandeur" in the acquisition of Heligoland, but the paragraphs above explain how the opportunity arose for Britain to use the island as a bargaining counter in order to acquire Zanzibar as a protectorate. Bismarck had set his eyes on Heligoland as a strategic acquisition for Germany but he skilfully downplayed it in the run-up to the negotiation. His first approach was made informally through a German journalist in an interview with a junior Minister in the Foreign Office. The Minister rebuffed the enquiry, but it was leaked to the Press and immediately became "the Heligoland Question" in London. When the negotiations with Germany over the status of Zanzibar were opened the idea of ceding Heligoland was denounced by several members of the House of Lords as a "betrayal of the people of Heligoland" who had benefitted from being a British protectorate. It became known that Queen Victoria herself had spoken to the Prime Minister against the proposal; and the Admiralty had warned of the danger of Heligoland becoming a German naval base. Despite the furore, the Treaty was concluded and Heligoland became part of Germany.

|

| German Port Facilities |

The German Emperor Wilhelm II, known to us as the Kaiser (1888-1918), lost no time in turning the island into a naval fortress. The harbour was extended with lengthy sea walls and the island became a naval fortress with gun emplacements tunnelled into the cliffs on the model of Gibraltar. This development combined with the surge in German naval construction during the early years of the Kaiser caused growing concern to the Admiralty, and dismay that Heligoland had been ceded to Germany under the Treaty of 1890. By the outbreak of war in 1914 Heligoland was a naval base of crucial importance to Germany, in particular for submarine warfare in the North Sea. After the war ended, the British government decided that the naval fortress of Heligoland should be demolished, and in 1920 a thousand German workers were sent to destroy the gun emplacements, fortifications and naval facilities. The question also arose: should Heligoland be taken back by Britain? Or given its independence? Or left in German hands? Despite the majority of islanders being in favour of returning under the British flag the government under Lloyd George decided that the island should remain German. It reverted in the 1930's to being a tourist resort, for mainly German visitors. In 1935 Hitler made a triumphant visit to the island to promote mass tourism as evidence that German sovereignty had been restored. In that same year he repudiated the disarmament clause in the Versailles Treaty and ordered the rebuilding of the fortress of Heligoland to go ahead. The island became a massive array of fortifications, bunkers and U-boat pens. During World War II it was once again a naval base for German submarine warfare, with a small airfield for fighter planes.

Towards the end of the war in April 1945, a thousand RAF aircraft dropped 7,000 tons of bombs on the island. The majority of the population survived in air raid shelters but the destruction made the island uninhabitable and it was evacuated. After the war, the island was used as a bombing range by the RAF, and in 1947 the decision was taken by the British government that for strategic reasons the island should be totally destroyed. The Royal Navy detonated 6,700 tons of explosives and literally blew the island up with one of the biggest bangs in history. In 1952 Heligoland was returned to German control, the town was rebuilt and the inhabitants allowed to return. It is now once again a holiday resort for tourists.

So ends this tale of two islands - Heligoland and Zanzibar - spanning just over 100 years from the Treaty that linked them. Heligoland became part of Germany and Zanzibar later became (nominally) a part of Tanzania. It is a tiny but fascinating chapter in British colonial history.