| Author’s Preface and Acknowledgements | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This account of the work of a latter-day District Officer in the long defunct Colonial Administrative Service had its genesis in the question posed by parents and relatives: ‘I know what you were and where you were – but what did you do exactly?’ Weekly air-letters home tended to record mundane domestic matters, and there was little time – or indeed inclination – to describe in any detail the manifold local matters which preoccupied me; what follows is only a partial answer to the question. There is little or no mention of the long hours spent poring over files, and compiling papers and memoranda on local concerns such as education, forestry, agriculture, the changing role of chiefs, or game control. Nor is there much reference to the time spent supervising the local treasury accounts, mulling over district development plans, or composing representations to distant seniors. Every job has its routine tasks which, though essential and perhaps absorbing to the practitioner, are less than enthralling to the outsider; but the work of a District Officer in Africa offered a range of interest which was probably unique. This book describes events which did not occur on a daily basis, but which were nevertheless typical, and indicative of the issues and problems which engaged us. It will, I hope, show something of the nature of district administration in Africa, and perhaps give some idea of why we found it so engrossing and satisfying. Before plunging into the narrative I would like to thank my wife Sylvia for her patience, forbearance, and support during our years in Tanganyika1, and for processing this text. I am also grateful to Tony Kirk-Greene, Colin Baker, John Iliffe, and John Cooke for their various advice, encouragement, and comment; and to the friends who have cajoled and bullied me into getting on with it.

I would also like to acknowledge the part played in our expatriate lives by our African domestic staff. After a few hiccups during our early months, we retained the services of two trusted and valued friends, Mzee Hamsini and Issa Saidi. With their families they accompanied us on our several postings until our departure. Thereafter we corresponded with them over the years until their deaths in the late 1980’s. Similarly the work of our African colleagues in both the civil service and local government merits recognition. Like employees everywhere – including ourselves – they were variously good, average, and indifferent. The poor were criticised, the good often taken for granted; but in general, with little or no training, they served their country well. In retrospect, we relied on them more than we acknowledged, and perhaps appreciated their contribution too little. Finally, a few words of tribute to that great survivor, the African peasant farmer, whose advancement was one of our primary concerns. He survived our good intentions, and will survive whatever his own governments may throw at him. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Introduction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No-one with an interest in British colonial history will need to be told what a District Officer was, but others may appreciate a brief description. All members of the Colonial Administrative Service were generically described as Administrative Officers, and collectively they directed and managed the main business of government, supported by specialist, technical, and professional officers in various functional departments. Those working in the Secretariat, the colonial equivalent of Whitehall, had designations related to the job they were doing. In the Provincial Administration, responsible for the provinces and districts, all Administrative Officers were known as District Officers (DOs); and in Tanganyika the senior DO in charge of each of the 56 districts had the courtesy title of District Commissioner or DC. In the mid to late 1950’s, Africans were increasingly recruited as Assistant District Officers, essentially a training grade but with every prospect of rapid promotion. During this period Dunstan Omari became the first Tanganyikan DC. The administrative cadre in Tanganyika probably numbered something in the order of 250, of whom perhaps 40 were out of the country on leave at any given time. The manner in which work was allocated between DOs was a matter for the DC, but between them they were responsible for the good government and administration of the district. As the senior official, the DC was the informal leader of the district team, which comprised local representatives of specialist departments as well as his DOs. His key personal responsibilities were to implement government policies, manage government expenditure, ensure the collection of revenue, and maintain law and order. He also had the important task of promoting and developing local government institutions and supervising associated staff. All DOs were magistrates, and in all but the largest districts the DC was also officer in charge of police and, if there was one, the prison. The DC was also, by default, the local representative of all departments which did not have a presence in the district. In short he was actively and intimately concerned with pretty well everything for which Government had a responsibility or interest. By European standards all this was very basic and unsophisticated and the resources available derisory, although even in an average district in a relatively backward territory such as Tanganyika, the DC and his colleagues managed several million pounds worth of expenditure annually2. It was this lack of sophistication plus the variety of experience offered which seduced us; only the brain-dead could fail to respond. The DO was very much a colonial creation, and there had been no comparable rôle in Britain since late medieval times. He was an expedient rather than a model, but – important in a poor country – cheap in relation to his wide range of duties. Where did a DO’s loyalty lie, and to whom was he accountable? In denigrating colonialism the critics usually fail to distinguish between the acquisition and retention of colonies on one hand and the process of disengagement foreshadowed for Africa in the early 1920’s, albeit not perceptibly begun until after the 1939-45 war, when it accelerated. They also tend to assume unanimity and complicity between Westminster, Whitehall, territorial governments, and the administrator in the field; this was by no means the case. We were not employed by the Colonial Office in London but by the government of the country in which we served, a government which had considerable discretion to act and legislate on its own account. It was answerable to both the British Government and, increasingly, its own people3. Similarly the DO was accountable to his territorial government, but also in varying degrees, albeit informally, to the people of his own district; the welfare of his people in his district was an unspoken but major preoccupation. To this extent most of us went native, with a strong inclination to respond to or advance local needs and priorities. This is not of course entirely true, but it is a fair generalisation; we were not merely agents of a distant government in Europe. The events described in this narrative are a record of one DO’s experiences in Tanganyika; they will not have been precisely replicated elsewhere, but were of a kind familiar to any former DO who served anywhere in British colonial Africa. Most of the incidents were directly related to work, but I have also tried to convey something of the flavour of domestic and social life in a rural district. In this I may have sold our womenfolk short, and my wife Sylvia would say that her recollections have a different emphasis from my own. Although aware of my official activities and preoccupations and unfailingly supportive, her main concerns were with running the household, raising the children, and latterly teaching the older of them the three Rs. Like many others she gritted her teeth at the oft-repeated observation that ‘of course, this is a man’s country’, with its implied acknowledgement of the lack of amenities and opportunities taken for granted by women in England. Absorbed by my work, I was largely oblivious to the deprivations and occasional hazards of domestic life; probably a majority of expatriate wives in remote districts enjoyed the life more in retrospect than in the event. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chapter One: How It Began | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stirrings In the years leading up to the outbreak of war in 1939 I attended a number of elementary schools in different parts of the country. North or south, metropolitan or provincial, they all had at least one thing in common – the celebration of Empire Day. The general holiday atmosphere, sports, and handouts of a cardboard box containing sandwich, bun, banana and orange made the twenty-fourth of May a day to be looked forward to. The years 1936 and 1937 were particularly heavy with imperial pomp and circumstance; King George V died in January 1936, not long after his Silver Jubilee; Edward VIII dashed quickly across the scene, leaving in his wake mementoes in the form of mugs, beakers, and aluminium medals distributed to the school population; and the next year there was the Coronation of George VI. To this came contingents of exotically-garbed Dominion and Colonial troops, and there were constant reminders that a disproportionately large part of the world’s map was coloured deep pink. During this period I discovered in the public library of my grandparents’ home town in Lancashire, a series of books recounting the adventures of one Trooper Ouless – nicknamed Useless – of the British South Africa Police4. Trooper Useless was an engaging hero, never likely to be promoted, a victim at every turn of Murphy’s law, and regularly falling foul of his Sergeant, Inspector, and officialdom in general. But like the Mounties, he always got his man – murderer, diamond thief, or the brutal farmer who was too free with his fists or whip. Indeed, to all intents and purposes he was a Mountie; same horse and bedding roll, same breeches, same revolver and holster; and the high-necked tunic was of the same cut, but a sober green instead of scarlet. Only the headgear was completely different, and Trooper Useless wore a khaki solar topee to prevent his brains from boiling in the tropical sun. Whilst – for all I knew – the background was as fictitious as the ripping yarns themselves, this boyhood reading sparked off an interest in Africa which was to propel me into the Colonial Service5 a decade and a half later. Halfway through the Second World War, aged fifteen or sixteen, I was captivated by Kenneth Bradley’s ‘Diary of a District Officer’ – so much so that I promptly wrote off to the Colonial Office, a little prematurely it might be thought, for whatever recruitment literature they had. The booklet ‘Appointments in the Colonial Service’ was distinguished by the Royal Coat of Arms, but otherwise resembled a school examination paper in layout and visual appeal. The prose style was correspondingly prosaic and understated, a colony dealt with briskly in a short paragraph. It was commonly reported that ‘good rough shooting is to be had in up-country districts’ or – less appealingly – of some low-lying coastal territory or island, that ‘Europeans may find the humidity trying (or enervating) in the hot season’, and that ‘children over the age of five are generally sent home to England’. The pay looked reasonably good, as I suppose any adult salary does to a schoolboy. Starting at about £400 (£10,000)6 a year and without promotion to dizzier heights, a District Officer could expect to get £1,000(£25,000) after nearly twenty years service – a princely income beyond my imagining. Another publication asserted that ‘only in the Colonial Service is it possible to live the life of an English country gentleman on a civil servant’s salary’. Not numbering the offspring of any country gentlemen amongst my acquaintances, I had only the dimmest conception of what this might mean; but it sounded all right – as if the prospect unfolded by Kenneth Bradley was not enough, with his description of life on safari in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), elephant in the Luangwa Valley, the District Office at Fort Jameson, and his hilarious encounter with buffalo bean, besides which, I was later to discover, itching powder was a very inferior product. Five years later, after a couple of years in the army, I was reading geography at Oxford, with Africa as my chosen region for detailed study, and as a special subject ‘the social and political geography of the British Colonial Empire’. In my final year I applied for appointment to the Colonial Administrative Service, putting Tanganyika as my first choice if selected. Climatic consideration played a greater part than perhaps they should have done, for I found an averagely hot summer day in England uncomfortable. West Africa would be too hot; Basutoland and Bechuanaland (Lesotho and Botswana) were tempting – but the level of recruitment derisory. Attention focused on the high plateau of East Africa. Kenya was better publicised and more developed; but here, I thought, Government’s freedom of action would be constrained by the white settler community. Tanganyika next door looked more promising ground; more ‘backward’, there would be more to do, and as a UN Trust Territory under international scrutiny, economic and political advance might be swifter than elsewhere. The first interview took the form of a very friendly chat with a District Officer from Northern Rhodesia on secondment to the Colonial Office. The board was a more formidable affair, officials ranged along the other side of a heavy polished table, faces dim against the bright summer sunlight. I have no detailed recollection of the interview, and of course on these occasions it is the questioning which largely determines which of one’s thoughts and motives are revealed for scrutiny and judgment. Certainly my own motives were mixed, but they were consistent. The idea of the wide open spaces and work which was not tied to an office desk had great appeal, and all my reading suggested that the work would be varied and interesting. By now I also had some knowledge of the problems of colonial development, and it seemed to me that there was a worthwhile job to be done; and whilst I did not at this stage envisage the early prospect of working myself out of a job, to play a part in preparing a dependency for eventual independence struck me as being a better way of spending my time than any of the alternatives on offer. And there was the further thought, essentially egotistical, that with so much to be done in the field, the opportunity to make a personal and visible contribution would be greater than in some highly structured monolithic organisation at home. My own country already had an abundance of what I assumed, not entirely correctly, Tanganyika wanted and needed; and perhaps I needed Tanganyika more than I needed Britain. I did not leave the interview light footed and confident, but felt that I’d had a fair crack of the whip and that if I failed I had only myself to blame. Preparations and departure Some weeks later a telegram announced ‘Subject to medical fitness and satisfactory degree result you have been selected for appointment to Colonial Administrative Service. Formal offer and allocation follows’. Both requirements were met, and I was appointed to Tanganyika. In the autumn of 1951 I returned to Oxford for another year to join twenty or so others on the First Devonshire Course. This was based in the Colonial Service Club under the direction of Jerry Cornes, a pre-war Olympic hurdler and former District Officer. We attended lectures on native administration, accounting, tropical agriculture, forestry, East African history, economics and development, Islamic history and theology, and anthropology. We did a rapid theoretical course on the construction of buildings, roads, and bridges; and on several warm summer afternoons we might have been seen under the guidance of Mr.Longland in the University Parks, making a simple compass traverse, marking in prominent buildings on a plane table, or laying out imaginary building plots with line and tape. They were simple techniques, later to be recollected with relief when surveying the line of a new road or putting up my first bridge – which in the event looked like a heap of debris thrown together by the river; but it worked! Most important, in an absolute sense, were language and law; failure to pass future examinations would result in a personal pay freeze. For the eight of us who were bound for Tanganyika7, and the one for Kenya, the language was Swahili; another group destined for Northern Nigeria, learned Hausa; and a very aloof young man who thought himself a cut above the rest of us was alone in grappling with Arabic, his posting the Aden Protectorate. He was welcome to it. In charge of our Swahili tuition was Robbie Maguire, a retired Provincial Commissioner from Tanganyika, silver haired and silver tongued; he was a spellbinder, each lesson carried along on a tide of anecdote, usually relevant and invariably entertaining. Explaining a particular construction he would relate how once, on safari, he was out shooting for the pot. As he walked up to the carcass of a shot antelope a figure appeared from nowhere, and reaching the dead beast a few yards ahead, observed with approval ‘ Itanitoshea’ - it will suffice me. Abdullah, his Zanzibari assistant, thought the Maguire technique rather frivolous, and favoured the more traditional method of learning by rote and repetition. Not a natural linguist, my own progress was further retarded by a preoccupation with persuading Sylvia Perry – partner at a summer ball the previous term, and secretary to the Professor of Zoology – to abandon all prospects of a safe, secure and comfortable life in England, marry me, and come to Tanganyika. Towards the end of our year’s training Robbie Maguire invited his class to tea on the lawn of his country home near Abingdon. In an informal valedictory speech he offered a final bit of advice; ‘Do not for Heaven’s sake think about marriage until you have done two or three years in the country’. It was good advice, and well meant. Afterwards, a little sheepishly, I confessed that a wedding was planned for the following month. Seventy years or so earlier, in more pressing circumstances, General Gordon was summoned by the Prime Minister and asked to undertake an ambiguous errand in the Sudan. The very same evening he caught the boat train at Charing Cross to connect with an eastbound steamer at Brindisi; those Victorians were no slouches. We still had five or six weeks to prepare for departure, and it seemed little enough. We started with an expedition to London to order essential purchases from a firm of tropical outfitters, Baker’s of Golden Square. It was perhaps as well that we were hard up, for there was no risk of being seduced by the more exotic and evocative equipment on display. Much of it had a decidedly pre-war look, but it was all indisputably new; a portable metal hip bath with a strapped-down cover, equally suitable for floating across rivers or porterage atop some curly head; a range of khaki canvas tents with or without built-in mosquito screens, and furnished with a variety of folding and collapsible furniture constructed of plain varnished wood and green canvas; pressure and incandescent paraffin lamps and humble hurricane lamps; water filters of varying degrees of complexity, and water purifying tablets; a primitive snake-bite outfit – a metal cylinder the size on one’s little finger with a sharp blade in one end to ensure a flow of blood, some potassium permanganate crystals in the other to rub into the wound; canvas water containers; gadgets for discouraging or demolishing ants, mosquitoes, flies. It all combined to make the heart beat a little faster, but left our exiguous bank balance largely unscathed; our main purchases were half a dinner and tea service and a plywood ‘cook’s box’ of heavy duty aluminium utensils; the colander still survives. In the clothing department a clerkly assistant drew attention to an assortment of spine pads – obsolete and ludicrous even in 1952 – and solar topees or ‘Bombay bowlers’. These two were faintly risible relics of an earlier age; yet they were, I believe, uniquely comfortable, extremely light in weight and well ventilated. And even then they were part of the wardrobe of expatriate officialdom in those territories – Kenya and Bechuanaland for example - where uniforms were regularly worn. I was tempted by a ‘double felt terai’ a broad-brimmed hat with two thicknesses of felt and hence rather heavy; but settled for an Australian-style bush hat which was lighter and a good deal cheaper. I was gently pressed to buy a white dress uniform, sun helmet and sword, bush jackets and baggy shorts, and a ‘sharkskin’ dinner jacket, but ended up with a white drill dinner jacket, a cummerbund, a budgetpriced Palm Beach suit which was to last me the next ten years, and the snakebite outfit. The footwear department was an eye-opener for someone accustomed to buy shoes at Bata or Lilley and Skinner. I had not imagined that such a range of shoes, boots and riding boots existed – and at such outrageous prices! We chose a sensible pair of brogues each; mine were Tricker’s at an extravagant £3 (£60)8, and four years later I sold them for a few shillings to an envious and importunate chief. He will now be dead, but they may well still be in use; they were good shoes. Mosquito boots were urged upon us, but unavailingly. I bought some canvas and leather army surplus ones for 30p and Sylvia acquired an extraordinary thigh-length pair from her sister who had lately been with her husband in the Gold Coast (Ghana). She never wore them. So far we felt that we were not conspicuously well kitted-out, and indeed all our purchases from the tropical outfitter, next seen in the Customs shed at Dar-es-Salaam, were neatly packed into a robust wooden box about three feet long and eighteen inches square. My final purchase did something to redress the balance, a single-barrelled folding shotgun of their own make from Cogswell and Harrison in Picadilly; I felt that I was really on the way. Our wedding in July was followed by a short week’s holiday in Somerset, a tour of my relations in Lancashire, and a few days with my parents and sister in Monmouthshire; then it was time for me to go, for Sylvia would not be accompanying me. At this time there was a regulation in force which prohibited a married cadet’s wife from joining him until he had passed his law and lower Swahili examinations, which rarely took less than a year; and a wife would interfere with the process of getting to know the country, or at least the district. Fortunately for us, this rule had already been inadvertently breached, and with the benefit of precedent, Sylvia could expect to fly out later in the year. We had a farewell night in London; it was hot and sultry following a blazing summer day full of exhaust fumes, a combination which makes London so good to get away from. The following afternoon, the heavy baggage having gone on in advance, a superannuated boat train from Liverpool Street carried us to Silvertown. Alighting, we turned our backs on the bulk of Tate and Lyle’s sugar refinery to face a street of Victorian shop fronts and cottages; on one corner was a pub with prominent cornices round doors and windows. Two hundred yards to the rear, and parallel to the main road, was the dock boundary, and sandwiched in between were terraces of artisans’ and dockworkers’ houses – the older ones of mellowed yellow brick, Edwardian ones grimy red, a little grander, and with bay windows. A few minutes walk took us to the gates leading into the King George V Dock. Beyond a long low brick warehouse with a serrated roof was a row of perhaps a dozen cranes, and –more important – the top half of mv Dunnottar Castle, painted in distinctive Union Castle livery; the hull was a shade of dirty pink with a hint of slate blue, the superstructure white, and the funnel vermillion and black. It seems a little ironic that my last contact with England should be with this dockland village, as alien in its way as any huddle of huts I might encounter in East Africa. For the next twenty years or so Silvertown went quietly to seed as the London dock industry declined, and then lay semiderelict for two decades, awaiting the next stage of Dockland reincarnation. Now, in an apt juxtaposition of old and new, London City Airport lies alongside the King George V Dock. In 1952 the age of cheap air-travel was a decade or more ahead. Sea travel was commonplace, and the ports of Southampton, Liverpool and London carried a large passenger traffic. From Southampton there was a weekly Union Castle sailing direct to Cape Town; from London, more irregular sailings round Africa, through the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal and Red Sea, and down around the Cape and back to London. There is an air of expectancy generated by anticipated departure, even on a channel ferry; but here in King George V dock there was a difference. This was not a ferry crossing or a cruise, and I was very conscious that at the other end was a new and very different way of life, a life of which I would become, or fail to become, a part. There were two parties of District Officer cadets on board; we had chosen a minority career for our own various reasons, but I imagine that most of us had similar reflections on the future between boarding and our last sight of the Lizard light. The voyage. Late in the afternoon those who were not sailing were hastened ashore, and Sylvia and I made our farewells; the sirens blew, hawsers were cast off, and the tugs manoeuvred us towards the dock gates. Amongst the crowd on the quay, vibrating with a hundred waving arms was Sylvia’s blonde head and her black and white ‘going-away’ outfit. Ahead was the curve of the Thames below Woolwich, and across the river Plumstead Marshes and the terra incognita of south-east London. We moved slowly downstream on a murky turning tide; well down the estuary we dropped the pilot and gathered speed, and the ship began to move to the sea. By mid-evening we were halfway down the Channel and the eight of us destined for Tanganyika alternated between the bar and the ship’s rail, the circumference of our circle occasionally touching that of a smaller group who were now employed by the Government of Uganda. A variety of reactions were apparent, but predominantly a relief that we were now on our way, lectures, seminars and essays behind us; and ahead, what ….. ? I wondered how much of Kenneth Bradley’s diary was still relevant; it had been written half a generation and a war ago, and many things would have changed. We could not have guessed how short our careers would be. The Bay of Biscay was unpleasant and the sunlit green hills of Galicia at the north-west corner of Spain the next morning were a reminder that Iberia is not all Castile and Andalucia. Down the Portuguese coast we passed sardine fishermen, their briskly bobbing boats an unwelcome reminder of the previous night. At Gibraltar we went ashore, climbed the rock, and had a ritual look at the Barbary apes. Thence to Marseilles, where there was just about time to visit the Chateau d’If, and we wondered whether the crowded troopship alongside our own was destined for Algeria or what was still French Indo-China.9 At Genoa we explored the waterfront and the hills encompassing the town to the north. And then we were away again, past Stromboli and Elba, through the Straits of Messina, round the toe of Italy, and eastwards towards Port Said. Early one morning in the lee of the long mole projecting seawards, we slid past the statue of Ferdinand de Lesseps – later destroyed in a fit of patriotic enthusiasm – and came alongside just astern of a black and rust-coloured vessel, the Ranchit, home port Karachi, and exuding a perceptible odour of stale curry. Further along the quay was a French ship of the Messageries Maritimes, with numbers of troops aboard, bound for Djibouti or Madagascar, both French colonies; close behind us, all white with pale yellow funnels, a multi-deck P and O liner with a cargo of British immigrants for Australia. At this time the British influence in Egypt was still strong, the Canal Zone occupied by British troops, largely National Servicemen doing two years obligatory service. However, Colonel Nasser had recently come to power, ex- King Farouk was in exile, and there was a noticeable sense of mixed uncertainty and expectation in the air. We ourselves, recollecting too vividly old soldiers’ tales of the iniquities of Cairo and Port Said, did not venture far from the ship. Indeed there was probably not a great deal to see and we contented ourselves with a visit to Simon Arzt’s famous emporium only a stone’s throw or two from where the ship was berthed. Having begun the voyage with only ten pounds by way of spending money I contributed little to the Arzt family fortunes and left with a cheap straw hat, regretting my impecunious condition.

On board the Dunnottar Castle the bumboat men and other vendors had turned the main deck into an oriental bazaar. Here one could purchase from a range of tropical fruits, and an infinite variety of camel leather goods, belts, purses, holdalls, suitcases, key rings, handbags, with or without motifs featuring the Sphinx, pyramids, and Pharaonic personalia; and many-hued carpets and wraps, most cheap and tawdry, some not. A gentleman with a cast in his eye urged me, unavailingly, to purchase a diamond ring which he demonstrated on a piece of glass which looked and sounded more like Perspex. On the side of the ship away from the quay the bumboats were ranged in a row, tied to the rail; below, the vendors would hold up their wares, and at the slightest hint of interest, an aide would haul them up on a piece of cord for closer inspection. In the nonstop haggling the passengers were invariably addressed as Mr. or Mrs. Mackintosh, the eponymous Briton of assumed thrifty habits. There were also the ‘gully gully’ men; gathering an audience, these engaging conjurers delighted young and old alike with their skilful legerdemain, magicking away day-old chicks and making them reappear from mouth, pocket, bosom and handbag. Finishing off with a deliberate appeal to the children, contributions were generous when the hat was passed round. In the early evening preparations were made for departure of the southbound convoy. The hucksters were hustled over the side and down the gangways, and as the time to cast off approached the bargaining became keener and noisier. My own booty comprised a camel saddle which served for years as an occasional stool, and a plaited leather riding crop which came unravelled in no time at all. Intending neither to ride nor beat my future staff, I cannot think why I bought it in the first place. At dusk we moved into the canal; the landscape was dull, but history stirred the imagination; this was the beginning of the Orient. Here things had changed little since Biblical times, but here also Napoleon’s eastern adventure had ended, Lt.Waghorn had pioneered the Overland Route to India in precanal days, and not far away to the west Hitler’s armies had been halted and turned back. The next morning we waited in the Bitter Lakes as a northbound convoy passed, and then entered the southern leg of the canal which led us into the Gulf of Sinai. For most of a morning we sailed between ramparts of sun-blasted jagged mountains of bare rock, occasionally passing small fishing villages or encampments on the western shore. To the east Mount Sinai rose from an uncompromising landscape, an entirely appropriate milieu for an Old Testament prophet. If Moses found a spring in that bastion of rock it was a miracle indeed. An hour or two later Sinai was out of sight, the shore of the Red Sea dim on the starboard side. It was about here that the heat and humidity began to be really unpleasant, and the significance and desirability of P O S H became clear; port out, starboard home. Four of us shared a cabin on the wrong –or starboard – side. Here, moving south, the ship’s steel plates heated up for six hours or so from midday onwards, turning the cabin into an oven in which sleep later was almost impossible. There was no air conditioning, and the ventilators blew warm air. Some cabins had metal scoops which, when fitted to the portholes, directed the breeze inwards; some cabins, like ours, didn’t. The Captain’s concession to this was to zig-zag the ship now and again so that cabins on both sides of the ship caught some of the southerly wind which was blowing up the Red Sea. At night some passengers slept on deck on chairs and benches; others stayed below on toweldraped bunks and sweated, and became acquainted with prickly heat. At this stage of the voyage we uttered uncharitable thoughts about the thriftiness of the Colonial Office, which had booked us tourist class instead of the first class accommodation to which we were formally entitled. We approached Port Sudan at five o’clock one morning and even at that hour the air burned its way down into the lungs; at noon the temperature was over 120F(50C), but it was a dry heat, and bearable. A few passengers went ashore to sample cold drinks and air-conditioning at the nearest hotel, and some of us took a trip in a glass-bottomed boat to have a brief look at the spectacular marine life. In the late afternoon the sky darkened in the west, and a sandstorm blew up - not a severe one, but enough to require us all to get under cover, with windows and portholes shut fast and ventilators closed down; it was dreadful. During the night we sailed for Aden. Aden Colony itself had no natural raison d’etre, and was a creation of British imperial needs by now largely obsolete, a fuelling station and staging post on the route to India and the Far East. A splendid harbour was backed by a range of awesomely spiky mountains, cubic miles of solid rock; and on a promontory overlooking the harbour were Government House, and Flagstaff House wherein resided the C in C Indian Ocean station. Along the waterfront at Steamer Point were the offices of shipping firms and bunkering agents, and a few shops and banks. A long taxi- ride away and out of sight of the harbour was Crater, the commercial centre for Colony and Protectorate (both now part of Yemen); and round the headland, the air and army bases and oil installations which were then a thread, still intact, in the fabric of Britain’s middle-eastern interests. At the time there was no hint to the passing traveller of the violence which was later to erupt and shatter the fragile confederation of sheikdoms in the Protectorate, and for some years leave the Russians established in force on Socotra island, and where the British bases used to be at Khormaksor and al-Mansoura. From Aden we set course to round the Horn of Africa, and some days later, soon after sunrise, we approached a low, sandy, palm-edged coast, and slipped into Mombasa’s Kilindini harbour. This was to be our Africa, and we walked into town, visited Nyali Beach and Fort Jesus, one of Portugal’s outposts of empire three centuries earlier. One afternoon we hired a couple of sailing dinghies from the obliging manager of the Yacht Club, and another day Tom Moon and I borrowed a pair oar from the rowing club. But we were anxious to be on our way; the ship was an inferno, with no ventilation for most of the day. To heat and humidity was added the clatter of cargo being unloaded and our ears rang as local African labourers chipped old paint off the superstructure with steel hammers as a preliminary to repainting. On the slow route round Africa, passengers came a poor second to cargo. Our stay in port was enlivened by Tom Moon’s engagement to Pat, a newlyqualified nurse encountered on the voyage. This was not unexpected, and married myself for only five or six weeks I had been approached for a little avuncular advice somewhere off the coast of Italian Somaliland a few days earlier. It was a good excuse for a party when we needed one. After an interminable week the ship sailed, made a brief stop at Tanga, and next morning we awoke off Zanzibar, with a fairy-tale view of the Sultan’s palace, and dhows at anchor or hauled onto the beach. There was the smell of cloves drying in the sun, and cloves by the ton in sacks awaiting shipment. I did not go ashore, and spent most of the morning in the sick bay. I had an appointment with a surgeon in Dar-es-Salaam. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chapter Two: Dar es Salaam and Manyoni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An inauspicious start The Dunnottar Castle had sailed from London on 13th August 1952, and dropped anchor in Dar-es-Salaam harbour on 13th September; I am not superstitious, but perhaps the dates were significant. From somewhere at the bottom end of the Red Sea, the ship’s doctor had been treating me for gastroenteritis. The symptoms did not respond and by the time we reached Zanzibar he had decided I had acute appendicitis. He radioed Dar-es-Salaam, and hardly had we got there and manoeuvred into the inner harbour a few hours later when, clad in a dressing gown more appropriate to an English winter than the East African coast, I was hastened down the ship’s ladder to a waiting motor launch. My fellow cadets were to see my baggage ashore and into the Customs shed. Our mutual goodbyes were necessarily brief, and I missed the shared round of appointments ashore and whatever celebration preceded their final dispersal to up-country districts; I saw none of them again in Tanganyika. It was dusk when I came round in a six-bedded ward in the Ocean Road hospital. Only one of the other beds was occupied, by a police officer who was to leave the following day. I was still fuddled, but our initial brief exchange was not to be forgotten. ‘Who operated on you, do you know?’ ‘Dr. X…….I think’ ‘God, you’re lucky to be alive, he’s usually stoned!’ The discomfort of the first couple of days was succeeded by boredom and an anxiety to get to my first post. Maudie Lee helped on both counts. She was a WAA10 in the department of Local Government and Administration, the one to which I now belonged; her daily visits to cheer me up were greatly appreciated. On the first occasion she told me I was to go to Manyoni. There is a consolatory and self-consciously cheerful way of breaking bad news, and it was clear from Maudie’s manner that Manyoni was not generally regarded as a plum posting. However, I was to be there for only a few months, and this was the least of my worries; it was all new, and there was much to learn. Of far greater concern was the unknown answer to the question – would I, after six relatively leisured years in the army and at university, be able to buckle down to a serious and demanding job?

Impressions of Dar-es-Salaam following discharge were fleeting. I spent a few days convalescing as the guest of a bachelor Administrative Officer, Geoffrey Allsebrook, who was serving in the Secretariat. Whilst he was at work I had a few undemanding duties of my own to perform. I walked round to Government House to sign the book recording the names of daily callers; His Excellency the Governor and Commander-in-Chief Sir Edward Twining, KCMG, now knew that I had arrived – or probably not, for in my ignorance, and following the example of the previous signatory, I entered the acronym ‘p.p.c’ (pour prendre congé) which announced my departure! This gaffe probably cost me an invitation to drinks, as HE usually made a point of meeting all newlyarrived cadets. Another walk took me to the office of Frederick Page-Jones, head of the Provincial Administration11 of which I was now a member; this was located in a prefabricated one-storey building, its door opening on to the street. It all seemed very accessible and informal, as did the white shorts and shortsleeved shirt which he wore; the only concession to formality was a tie, a distinction which I was to discover separated the Secretariat sheep from the upcountry goats. I also had to call on the Chief Secretary, who formally welcomed me to the Service, and administered the oath of allegiance. On a more mundane domestic errand I made my way to see Bill Mate, the Government Passages Agent, a friendly and obliging man whose main task was to assist officials moving themselves and their families into and out of and around the country between postings. On this occasion he got a berth for me on the next overnight train to Dodoma where I was to recuperate for a further week, and undertook to have my heavy baggage freighted up to Manyoni . This now included a newly-purchased paraffin-operated Electrolux refrigerator against which the Accountant General had made me a loan. Our imported effects were all dutiable; there was no discretion, and I was allowed half a month’s salary in advance – twenty five pounds – to clear our small wooden case and a few trunks through Customs; a mean beginning I thought.

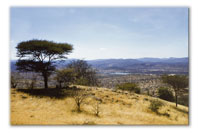

During my brief stay in Dar-es-Salaam it was the street scenes and sounds which registered most strongly, particularly of course those which were distinctively African. The streets were ablaze with the deep orange blossoms of the flamboyant trees – a variety of acacia – and rarely was a mango tree or palm not visible. Also flanking the streets were open storm drains into which rubbish was apt to be thrown and where, in consequence, pi-dogs scavenged; and kites too, when not wheeling overhead, mewing like kittens. In shop doorways Indian traders stood, and on their verandahs black and brown-skinned tailors worked on their treadle sewing machines. At the bottom of Acacia Avenue was the Askari Memorial, a life-size bronze of a soldier of the King’s African Rifles, commemorating the service rendered by Tanganyikan askaris in two world wars. Along the beach edging the harbour fishermen landed their catches from outrigger canoes, loafers sat and laughed and chattered, and passengers from one of the anchored ships aimed their cameras. As well they might, for no-one who has been through Dar-es-Salaam could be indifferent to that curve of sand framing the harbour, edged by palm trees behind which are the white, red-roofed buildings of the German and British colonial periods, and the two cathedrals. There were the smells too, not unpleasant, but certainly distinctive – a faint but predominant hot-house taste in the air, compounded of rotting vegetation, fruit and seaweed, drying refuse, and an occasional whiff of drains and diesel fuel from the harbour. It was a smell first encountered in more intense form at Port Said, and later in Port Sudan where the mid-day sun put a heat-tempered edge on it. Up-country the chemistry was different, a pot-pourri of hot dust and wood smoke, with a varying injection of evaporating animal urine and, at the right time of year, the scent of acacia blossom in the bush. Journey Up-Country My departure from Dar-es-Salaam railway station is not one of my more cherished memories. The train left at 9.30 at night; mosquitoes swarmed, and clouds of insects swirled round the dim overhead lights. It was hot, over ninety degrees (+30C), and clothes hung limp, clammy, and soaked with sweat. I had more hand-luggage than could comfortably be fitted into my sleeping compartment, a circumstance which my travelling companion, a Government doctor bound for Iringa, must have found tiresome. The wire gauze over the windows kept out air as well as mosquitoes; I felt, and smelled, like a newly wrung-out dishcloth. By the middle of the following morning the discomforts of the night were forgotten. Up at the front, a wood-burning Garrett locomotive towed us along the metre-gauge track at a steady twenty-five miles an hour. One of the attractive features of the antiquated rolling-stock of East African Railways and Harbours at the time was a little open-air gallery at each end of the first-class cars. A wrought-iron balustrade prevented the traveller from falling off, and the extended roof kept the sun at bay. It was a delight to sit on the iron floor, arms looped round the upright rails, legs dangling in space, and watching Tanganyika unfold. In truth it was not a riveting landscape. An occasional line of low blue hills would advance, turn brown and recede to blue again, and little patches of cultivation showed up green but in general it was brown land, brown men, brown cattle, and brown houses. Two hundred miles or so of brown; we had passed the green bit and the Uluguru mountains during the night. It was a sunburnt brown, but if the sun burned the landscape to a uniformity of colour it also enriched it with a range of shades from bleached pale yellows to tawny and dusky browns – with black where the sun did not reach. At Dodoma12 I stayed a night or two with the Australian DC John Pearce and his wife, met my Provincial Commissioner, Leonard Heaney, and then moved for a few days into the Railway Hotel. In retrospect this was an undistinguished building, but it seemed wholly appropriate to its dry and harsh surroundings. It was square in plan with an internal courtyard. The rooms were cool and shaded, with dark polished wood floors and furniture, and each opened onto a small private balcony. Here, with the aid of a few rehearsed phrases of halting Swahili, I hired Athmani, our first cook. In the event he was not a great success and we parted company a few months later. Early on the next Monday morning I was collected by the Dodoma Resident Magistrate (RM) in an Austin A40 pick-up; he had a civil case to hear in Manyoni. The journey was only eighty miles, but it was a poor road and the RM was a cautious driver. Athmani, sitting in the back, slept most of the way. It could not be said that the country through which we passed was beautiful; but, drier west of Dodoma than it had been to the east, it impressed by its sheer harshness. In fact it was semi-desert, punctuated visually by outcrops of rock and a scattering of baobab trees, thorn bush, and an occasional patch of withered millet. We dropped gradually down the eastern slope of the Rift Valley, and then drove for fifteen miles across the barren floor of the Bahi Depression. Around Saranda there was water, and an oasis of green trees; elsewhere just bare earth and dust, thorn thickets, and a clump of doum palms here and there. From time to time we saw a Gogo13 cattle herder accompanying a few tiny under-nourished beasts, sometimes a donkey amongst them carrying one or two leather panniers. Then we tackled the steeper western escarpment. The train needed two locomotives to push and pull it to the top at a good walking pace; the R.M’s pick-up was somewhat faster, but its radiator was boiling by the time we reached the top. We rested awhile, and I took in the view to our rear, where the Rift Valley lay spread out below us, running north to south – and going on and on to the Dead Sea in one direction, and down to Nyasaland (Malawi) in the other. The valley side was well-wooded, and I enjoyed my first sight of wildlife in the form of a flock of green and red parakeets squawking amongst the trees. From here onwards we climbed only very gently, and then levelled off, driving first through light miombo or open woodland and then through thorn bush until suddenly without warning, we were at Manyoni. Manyoni I was not disposed to be critical – it was all new and exciting; but by the end of the three months I was there, and although it had not begun to pall, I recognised its limitations in terms of experience and opportunity to learn. The learning began at once, sitting in with the RM as he dealt with the litigants in a civil case in the DC’s office. At lunchtime I was told that the DC – Bill Helean, a New Zealander – had gone to Dodoma the previous day accompanied by his wife Ethel, for hospital treatment; I also learned that there was an outbreak of bubonic plague at Itigi, forty minutes drive to the west along the railway. Completely unsighted, I consulted the Provincial Medical Officer in Dodoma over the phone; he assured me that all I needed to do was ensure an adequate supply of gammaxane powder to the African public health staff at Itigi who were engaged in eliminating rat fleas. It was a relief when Bill Helean returned three or four days later. There then began a more purposeful process of learning on the job. I was pitched into the Native Treasury for afternoons at a time – hot, sticky afternoons under a corrugated iron roof – where Hassan the Treasurer showed me how the accounts were kept; instruction was none the easier for being conducted in Swahili. A few weeks later I was assumed to be competent to carry out the monthly check on his books. As a Third Class Magistrate, and with the aid of an interpreter, I began at once to hear straightforward cases in the District Court; and within three weeks heard my first Preliminary Inquiry (PI), a process whereby a magistrate determines whether or not a person charged with serious crime beyond his jurisdiction should be discharged or sent for trial by the High Court; in this case a man had shot and killed a neighbour with a poisoned arrow. I was sent out to investigate and settle a minor boundary dispute between two adjoining chiefdoms; and on a similar occasion incurred Bill’s displeasure by giving away a small piece of Manyoni to Singida district, whose delegation was led by Geoff Thirtle, a DO a year ahead of me in experience and fluency in Swahili. I uttered warnings to Fazal Ladha, a local trader who was selling weevily flour, not yet realising that most flour was infested to some degree, and best sieved before use; laid out the site for a new primary school; and annoyed Bill yet again by failing to arrest a man I had been specifically sent out to pick up for threatening violence to the outposted police corporal at Itigi Junction. The culprit was engaged on urgent locomotive maintenance, and the engineer in charge promised to send him in later, which – to my relief – he did. On another occasion Bill required me to accompany Sub-Inspector Boniface and a few constables on what he described as a ‘tax raid’ in Manyoni settlement, which comprised no more than thirty or forty dwellings. This involved knocking up the occupants in the small hours and requiring adult males to show their tax receipts; bleary-eyed and grumbling, most of them did so. Defaulters were expected to show up next morning cash in hand, or face prosecution. I found the whole process demeaning and personally embarrassing; it achieved nothing which could not have been done conventionally by one or two tax clerks during the day. In the event this experience turned out to be irrelevant, and I never came across the practice anywhere else, nor ever initiated it. A daily diversion was the five minutes or so spent with Rajabu, the imprecisely-designated Station Hand. A slight man, wearing a navy sweater, khaki shorts, and a military manner reinforced by a sergeant-major’s swagger stick, he presented himself early every morning to consult me about the disposition of the current contingent of extra-mural prisoners. In stations where there was no prison, offenders given short sentences were required to undertake some form of public work until they had served their time. They slept in very basic dormitories, and during the day carried out a variety of tasks – typically cutting grass along the road verges, clearing ditches, watering plants, chopping firewood, and so on. Rajabu supervised them and dispensed their daily rations. One afternoon, at their request, I tried to mediate in a domestic dispute between husband and wife. Mansur was a plump and prosperous middle-aged Arab timber merchant with a tuft of grey beard, and wearing an orange turban, white calf-length tunic, and sandals; in the sash around his waist was a curved dagger in a splendid silver sheath. His African wife was probably in her late teens, attractive, coquettish, and swathed in a pair of red and yellow patterned kanga – matching rectangles of cloth – one round her waist serving as a skirt, the other draped over her head. Formal appearances in a District Court were not unusual, especially where there were cultural or ethnic differences, or there was a conflict between local customary law and, say, Islamic law. But this was an informal affair; no doubt both parties had already consulted relatives and friends, and now they sought a neutral opinion and an indication of what would be involved in going to law. Listening carefully, and with the help of an interpreter I felt very inadequate in the rôle of Dutch uncle. At the end I could only hope that the voice of reason and authority carried some conviction, and that a divorce would be averted. I rather doubted it. Medical provision in Manyoni was exiguous and came in the solitary form of John Kunsinda, a Rural Medical Aid with a year’s training, limited diagnostic skills, and a range of very basic drugs at his small dispensary. John was a tall, cheerful, and kindly man in his mid-thirties. We never had to put his skills to the test, and our occasional conversations tended to revolve round public health matters. One singular personal characteristic lingers in the memory; he had a conspicuously ill-fitting set of false teeth which rattled and clacked when he spoke, and appeared to have a life of their own. We assumed that he had picked them up second-hand as a preferred option to toothlessness, but he quietly declined the offer to help him get a set that fitted. Manyoni district was not very fruitful ground for missionary activity; there was a small Church Army mission at Kilimatinde, on the edge of the Rift, and below it, at Makutopora, a brace of CMS (Church Missionary Society) ladies ran a leprosarium. One of these was an Australian who turned up from time to time in a small Fordson van to seek assistance from the District Office; perhaps she felt she had some special claim on a fellow-Antipodean. At any rate she had a certain facility for getting under Bill Helean’s skin. He was a bluff and hearty man, and a bit of a bully, and it was a matter for surprise and amusement that he could be so easily rattled by this earnest spinster. She had recently wanted us to disperse discharged patients from the vicinity of the leprosarium where, she complained, they were seriously depleting the mission stocks of food. Bill had not unreasonably declined, suggesting that they stayed precisely because they were fed, and would drift off home if this largesse ceased. One afternoon I was working on some papers in my office when Bill dashed in through a connecting door, having spotted the Fordson van approaching; ‘It’s that bloody woman from Makutopora again…. tell her I’m on safari ….get rid of her and let me know when it’s all clear’. With that he let himself out through a rear door leading to a small inner compound. I did my duty and basked in Bill’s approval for the next day or two. For a man who was normally pretty robust in his dealings with the public, this was a new side to his persona.

The only other non-official Europeans in the district were the Robbie family; they eked out a precarious living on a small plantation, originally German-owned, but now leased from Government. I visited the family only once, and wondered how they could subsist in such an unpromising environment for agriculture; one could only admire their fortitude. * * * Most evenings were spent poring over the Laws of Tanganyika and A Handbook for Magistrates, Local Government Memoranda14, and my Swahili vocabulary. If law and language examinations were not passed within two years there would be no more salary increments. This compelling though scarcely generous carrot as a reward for diligence was reinforced by two sticks. A DO cadet in his first tour was not allowed a car loan as were his more senior colleagues; the idea was that he should be out and about on foot getting to know people and country. The second stick, the conditional ban on wives accompanying their husbands on first appointment, has already been referred to. However, with the benefit of precedent, Sylvia was booked to fly out in November. The reasoning behind the tattered prohibition now became clear; less of my time was spent on books, more on preparations for Sylvia’s arrival – having a bath installed and a privy built, staining the woodwork of our little thatched brick rondavels with a solution of potassium permanganate, and acquiring a few more sticks of furniture. There was nothing much I could do about our water supply, which came out of a shallow well five yards from the front door, and which was so muddy that the ceramic elements in our water filter rapidly clogged and had to be cleaned twice a day. Every expatriate household had a filter; these were upright cylinders about 2ft (.7m) high, of glazed earthenware or aluminium. Into the upper chamber went the boiled water, which was then filtered through 3 hollow porous ‘candles’ into the lower chamber, from which pure water was drawn by tap. The ‘candles’ normally needed cleaning only once a week. Rubber washers within the filter ensured that the water acquired a slight taste; this was partly dispelled by refrigeration, wholly so by the addition of fruit cordial or juice. The kitchen did not lend itself to improvement; it was typical of the period, and assumed that the colonial wife was inept, idle, or both, and that cooking would be left exclusively to the cook. It was built at a distance from the house, and was equipped with an iron wood-burning stove, probably cast about the time of the Boer War, bought in bulk, and issued for the use of generations of colonial officials thereafter. In the capital and larger towns, electric cookers had begun to make their appearance; two years later we graduated to an indoor kitchen, but one still equipped with an iron stove; and for our last few months in the country we enjoyed the luxury and decadence of a bottled gas cooker. Sylvia duly arrived by the morning train. She had been accompanied on the last part of her journey by the DO, Geoff Thirtle, who had bested me in the boundary dispute, and who was on his way back to Singida after a visit to provincial headquarters. To Sylvia’s credit she did not burst into tears when she saw her new home, for in truth it was very basic; two round rooms twelve or fifteen feet in diameter joined by a small mosquito-proofed verandah. Until I moved in it had been a rest-house, used by officials on tour; I rather resented being docked the regulation ten per cent of salary by way of rent. However, it was only a temporary home and we were to be transferred to Kondoa at the end of December. With this in prospect, and partly because we were still very new, we did not make any close friendships in the tiny expatriate community in Manyoni.

Apart from Bill and his delightful wife Ethel, this comprised Toby Reilly, a middle-aged Crop Supervisor, and Tony Mence, a young Game Ranger who always looked the part, and both bachelors; and there was Bertie Hall, the District Foreman, and his wife. We played tennis together, visited each other’s houses for drinks or dinner, and went down to meet the train twice a week to see who was passing through. I enjoyed Manyoni, but was scarcely more permanent than the train passengers who passed in transit, thankful that they were not stationed there. In retrospect I suppose Manyoni’s reputation was justified. The district, with an area of just under 11,000 square miles and a population of only 59,000 was one of the largest and most sparsely populated in the country, and also one of the least developed; like most of Central Province it was extremely dry. Its eastern boundary lay in the Bahi Depression, its western part covered with almost impenetrable thorn bush described on the map as Itigi thicket. Between escarpment and thicket was mixed woodland and thorn bush, with patches of half-hearted cultivation, and occasional expanses of mbuga which were swampy in the brief rains, and approximated to parkland in the dry season. Apart from the escarpment, with its breathtaking vista to the east, the district was scenically extremely dull, epitomised by the view from our back door where, after twenty yards of bare sand and dust, the thorn bush began, and went on and on and on. In this inhospitable landscape lived the Gogo, a small tribe of pastoralists, still semi-nomadic, but becoming increasingly settled. They demanded little other than to be allowed to live as their tradition prescribed, with minimal interference from central authority; of Government they expected only that relief be provided in times of famine, and that rural medical services be extended into the remoter parts of the district; education was not a priority. Manyoni settlement was wholly undistinguished. Fewer than a dozen decrepit dukas or shops huddled in the dust along two sides of a desiccated market place. The shops referred to here and elsewhere were indeed shops in the sense that goods were exchanged for cash; in other respects they were not quite the shops we know. Construction ranged from daub and wattle with earth floor, to cement block, with roofs of either grass or corrugated iron. Typically the sizeable front room of the building, usually windowless, was the shop; entry was by one or two wooden double doors, left open during business hours, which ran from early morning until late at night. Along the walls were plain wooden shelves carrying a range and quantity of commodities contingent upon the requirements of the local clientele and the credit-worthiness of the proprietor, who lived behind rather than above the shop. On the floor were 4 gallon tins of paraffin, ghee, sunflower and sesame oil, sacks of rice, flour, sugar and beans, bundles of hoe heads, pangas, (machetes), buckets, cooking pots and assorted hardware. There was usually a limited range of cheap fabrics and kangas, and there was sometimes a ‘tailor’ available who could run up simple garments. In the case of Manyoni, the few dukas peddled a severely limited range of goods, mostly of the poorest quality, for the Gogo domestic economy was not such as to sustain a flourishing trade in even the most basic consumer commodities. At the other end of the main street was the Boma15, a ramshackle singlestorey mud-brick building which an optimistic Greek had once owned and run as a hotel. At the other end the shops and houses soon thinned out, and a hundred yards or so beyond the market the road disappeared westwards into the bush, accompanied by a single telegraph wire suspended from metal poles, a symbol rather of isolation than communication. Prior to Sylvia’s arrival I had made a few rather inconsequential safaris, educational rather than useful. I accompanied Toby Reilly on one of his field trips, the better to understand the nature of his work. On another I was sent to make some assessment of food reserves in the remote south of the district, reached along dusty imperceptible tracks. On this occasion I just about preserved my savoir faire when, shortly after stepping out of the office Landrover, an apparently crazed old man about five feet in height rushed at me brandishing a spear and shouting incomprehensibly, stopping abruptly two or three paces away; this, it was solemnly explained, was by way of being a traditional greeting to strangers. It might easily have been misinterpreted. It was possibly a commonplace with newcomers, but camping under canvas in the bush initially occasioned some anxiety regarding the habits of predatory carnivores, and on my first couple of outings I took precautions with deterrent fire and hurricane lamps, and carefully laced up the tent before sweatily and wakefully retiring. Within weeks, I concluded that this was nonsense; the risks were negligible, and an open tent was cooler, especially if open at both ends. Later I often dispensed with the tent and enjoyed the night sky. Sylvia’s first safari experience was not a happy one. We set off in the Native Authority (NA) truck; first stop Itigi, to check on the aftermath of the plague outbreak, and then south-west to carry out a routine check on the local court and dispensary at Ukimbu, where we were to spend the night. The domestic arrangements were primitive. A small daub and wattle structure purporting to be a rest-house had recently been thrown together; it comprised a single windowless room, with earth floor, about eight feet by six. Outside, a door was propped against a wall, but the frame into which it would eventually fit had not yet been installed. Towards evening the sub-chief casually remarked that there was a man-eating lion in the vicinity, at which moment the lack of an effective door assumed a larger importance. It now seemed a mere trifle that Athmani had brought only one camp bed; thirty inches wide, this promised us an uncomfortable night rather than a cosy one. When it was time to turn in, I wedged the door into the aperture as best I could, loaded my shotgun with heavy SSG shot and put it under the bed, just in case. It was an unforgettably excruciating night. This then was the background of our introduction to East Africa and of my own initiation into the craft of district administration. There was more than enough to engage the interest and energies of a raw cadet, but Kondoa already beckoned. It was by all accounts a more complex and developed district, politically more sophisticated, and with formidable problems of overgrazing and soil erosion. The DC was also said to be an able and thoughtful administrator, and such criticism as I heard inspired approbation rather than anxiety. Shortly before Christmas we set off in the Native Authority 3-ton Bedford, Athmani curled up amongst our goods and chattels in the back, and Sylvia with me in the cab, she nursing a recently acquired three-month old pup, Oliver Cromwell. It was a good time to arrive, and we were pitched into the round of jollifications without any of the disadvantages of preparation. As if the Christmas and New Year festivities were not enough, the DO whom I was replacing was married during the few days of our overlap. We thus met all our colleagues in a relaxed holiday atmosphere, although the confrontation between their concentrated African experience and our own lack of it was a constant reminder of our shortcomings. On New Year’s Eve our next-door neighbour Douglas Turner threw a party for the rest of the station. Shortly after midnight the festive mood was dispelled when Douglas’s cook came in with the news that the man who looked after the rest-house two hundred yards further up the hill had been found hanging by the neck from a beam. Jimmy and Douglas went to investigate, and the party petered out. A few days later I was deputed to conduct the inquest, and was grateful to have observed one of the East London coroners at work the previous year. It was a sad case, and suicide was the inevitable verdict; the cause of death was confirmed by the government doctor, and there was no evidence of foul play. The caretaker had been a conscientious man, of a rather shy and retiring disposition, and it was reported that he had recently been taken to task for some minor dereliction of duty, which had upset him; but it was unlikely this alone had prompted him to take his own life, and his family could shed no further light. After this initiation I conducted perhaps half a dozen inquests a year; most unnatural deaths were clearly either accidental, murder, or manslaughter. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chapter Two: Dar es Salaam and Manyoni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background The staffing of a district depended on its size, population, and the level of economic and political development; Kondoa was middle of the road in all respects. Less than half the size of Manyoni district, it had three times the population, and problems deriving specifically from localized overgrazing and overpopulation. The team of expatriate officials was presided over by the DC, Cecil Winnington-Ingram, a bachelor in his late thirties. There were two DO’s, Jimmy Hildesley, ex-Indian army, divorced but shortly to remarry, and myself. The only other bachelor on the station was Douglas Turner, the Provincial Tsetse Officer; he was, like me, in his mid-twenties, and although having provincial responsibilities had chosen to live in Kondoa rather than Dodoma. The others were all married, mostly with children either living with their parents or away at boarding school in Tanganyika. Jack Allen, the Settlement Officer, had been brought up in Tanganyika; he was there to ensure the medical treatment, rehabilitation and resettlement of a group of Sandawe from the western part of the district who had contracted sleeping sickness a year or two earlier. Mr. Tymkow, with an unpronounceable first name, was an excitable but congenial Pole who, with many of his compatriots, had been taken prisoner by the Russians in 1939; they were later allowed to leave via Iran on condition that they were not engaged as combatants by the Western Allies, and saw the war out camped in East Africa. Mr. Tymkow (he was always Mr.) was the District Foreman, responsible for all Government stores and the maintenance of buildings and district roads. David Goode, born and raised in India, was the able agricultural Field Officer, whose misanthropic manner disguised a generous and helpful nature; he was engaged primarily in agricultural extension work. The Veterinary Officer, Horst Retzlaff, was a German married to a Swedish countess, and concerned with animal husbandry as well as health. The small and rather primitive government hospital was run by an Indian, Dr. Apte, assisted by an eccentric Scottish nursing sister, Marguerite Hartley, who later died prematurely in Nigeria. An African Schools Supervisor kept primary and middle schools up to scratch. Such was senior officialdom in Kondoa at the time of our arrival. Together and in collaboration with the Native Authorities16, assisted by mainly African staff, they were responsible for the administration of the district, and insofar as limited budgets permitted, its development.

Set a little apart from the rest of us was the Seychellois Benoiton family. The husband was responsible to the Provincial Engineer in Dodoma for maintaining over 100 miles of the Great North Road, and was based in Kondoa purely for reasons of convenience; he had no special interest in the district. Of the local junior civil servants, there were three clerical staff working in the District Office, the senior of whom was Selemani, a Somali. He was efficient, but his officious manner, lack of humour and air of superiority did nothing for his popularity, and he must have been a very lonely man. The busy cash office was run by the quiet and self-effacing Mr. Padmanabhan, recruited from India, and assisted by an African clerk; the bulk of incoming revenue was collected by a contingent of tax clerks. There were perhaps twenty police constables, managed by Sub-Inspector Gurmuk Singh, a young Sikh, and an African sergeant. The prison was under the day to day control of a Head Warder, of warrant officer rank. Common to all Bomas were our messengers, of whom more anon; at this stage I did not appreciate their unique value. The Government station was separated from the township by the Kondoa river, most of the buildings dating back to the time when Tanganyika was German East Africa. The Boma, approached by a tree-lined avenue, had been a combined administrative centre and fort, and on a hilltop ten miles or so to the southwest were the remains of an old heliograph station, part of a network covering the colony; weather permitting it had been possible to flash messages – over 700 miles – from the coast to Lake Tanganyika within hours. All but two or three of our bungalows were solidly Teutonic, with thick walls and wide verandahs; they were thus relatively cool, and we were glad to move into one after several months in cramped temporary quarters.

Kondoa had been the site of a major action between British and German forces in the 1914-18 war, during which about two thousand German offcers and NCO’s leading African troops had tied down a much larger British, Dominion and Colonial army; they were still undefeated at the armistice. There was a further reminder of those days in the person of Paul Tchoepe, a diminutive German in his fifties, who had been chauffeur and orderly to General von Lettow-Vorbeck, the German commander-in-chief. When invited to dinner, and with little encouragement, he would relate with glee how the quick-witted Germans regularly put one over on the plodding British. Now he was the proprietor and occupant of a small hotel which had been left high and dry when the main north-south road by-passed Kondoa two miles to the east. He earned a living doing a variety of contractual work for Government and the Native Authority. Down near the river, opposite our tennis court, was a graveyard, shaded by mango and casuarina trees; the Commonwealth War Graves Commission remitted a small annual sum with which we employed a caretaker to keep it tidy. The war graves had been supplemented by that of a DC, Mr. Darling, who had come to an untimely end falling out of a tree some time between the wars.

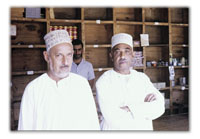

Just below the graveyard the road ran into a concrete drift or ford, beyond which was Kondoa township, a bustling place with tree-lined streets, and a busy market. Its population numbered little more than a thousand, including a number of Indian and Arab traders, two or three of whom specialised in supplying groceries to the expatriate community. Prominent amongst these were the smooth- talking Ali Hamad Amour, a handsome Arab, and Abdullah Sajan, a noisy and argumentative Gujarati, whose wife made the best samosas west of Bombay. The township also boasted a playing field, a small mosque, and two Christian missions tactfully located at opposite sides of the settlement. The sizeable Roman Catholic mission had several expatriate staff, and ran a dispensary and middle school; by contrast the small Anglican CMS (Church Missionary Society) church was presided over by a solo African pastor.